Scrapping NHS England

Dear Friend,

Apologies for the delay in today’s email – I got caught up in the Football League Cup final, which pushed back the usual posting time. Unfortunately, my team, Liverpool, didn’t come out on top, so it’s been a tough week for us supporters.

You might also have noticed that the “Drug of the Week” section has leaned heavily towards oncology in recent weeks. That’s because I have my oncology specialty training interviews coming up next week, so I thought I’d take the opportunity to revise while preparing this mailing list.

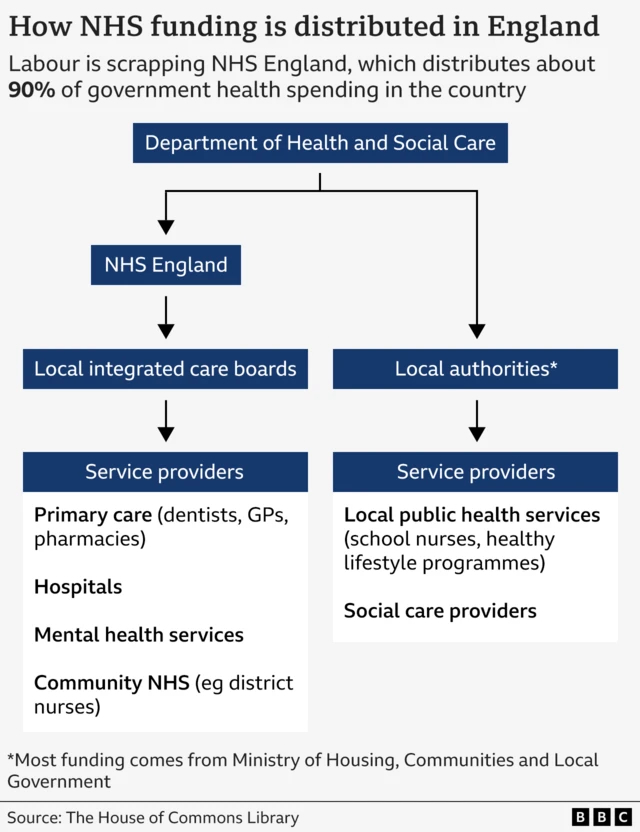

This week, the UK government made a major announcement about the future of healthcare in England that will directly impact doctors, patients, and the NHS workforce. The decision to scrap NHS England has raised a number of questions and concerns. As a medical student or junior doctor, it’s important to understand the potential consequences of this reform on your training, future practice, and patient care.

For the avoidance of any confusion, this does not mean the government is getting rid of the NHS. NHS England is an executive non-departmental public body of the UK government that oversees the delivery of healthcare services in England – it basically helps to manage the NHS. Hospital and medical treatment will still be free at the point of care – but there will be changes in how it is run.

What Exactly Has Been Announced?

The government has decided to dismantle NHS England as part of a broader restructuring of the NHS. This will involve changes in governance, leadership, and the structure of the NHS at a national level. The move comes as part of the government’s ongoing efforts to “reshape” healthcare delivery, focusing on greater integration between services, regional leadership, and decentralised decision-making.

Key Points of the Announcement:

- NHS England, the body responsible for overseeing the NHS in England, will no longer exist in its current form.

- Responsibility for healthcare delivery will shift to a more regional and locally led approach, with Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) taking on a larger role.

- New leadership structures will be put in place at both regional and local levels, and some decisions currently made centrally will be devolved to local bodies.

How Does This Affect Doctors?

1. Changes in Governance and Leadership

- The removal of NHS England could mean a shift in how policy and decision-making affect the day-to-day running of hospitals and clinics.

- Leadership could become more fragmented, with individual regions having more autonomy. This might impact your career progression, job allocations, and workplace environment as decisions will be made at a more local level.

2. Training and Career Development

- The decentralisation of decision-making could lead to changes in how training programs are structured and funded.

- Different regions might have varying approaches to clinical placements, rotations, and educational resources, which could affect your opportunities as a junior doctor.

- While there may be benefits in terms of localised training opportunities, there may also be potential disparities in the quality and access to these programs depending on where you are based.

3. Impact on Workload and Job Security

- Local healthcare systems will likely be under increased pressure to meet patient demands with potentially fewer central resources.

- The fragmentation of healthcare services might lead to variations in funding, staffing, and resources across different regions, potentially influencing your working conditions and job security.

4. Pay and Contracts

- As the leadership structures change, there could be implications for NHS pay and contracts. These changes may affect your remuneration and the stability of employment contracts across different regions.

What About the Patients?

The impact on patients is also significant. The goal of the restructuring is to provide more locally tailored healthcare services, which could theoretically lead to more integrated care and shorter waiting times. However, there are concerns that the changes could also cause disruptions, particularly if funding and resources become unevenly distributed across regions.

- Access to Care: Depending on the region, patients could see improvements or worsening in access to care, depending on how effectively local systems are able to adapt and manage resources.

- Equity of Service: There is a risk that healthcare disparities across regions could widen, with some areas potentially receiving better care than others, depending on local leadership and funding.

Conclusion

The announcement this week marks the beginning of a significant shift in the NHS’s structure. While the government promises that the changes will improve care, there are many unanswered questions about how this will affect both the medical workforce and patients. As medical professionals, we will need to stay informed, flexible, and engaged as we adapt to these new structures.

Hope you have a good week!

Drug of the week

Irinotecan

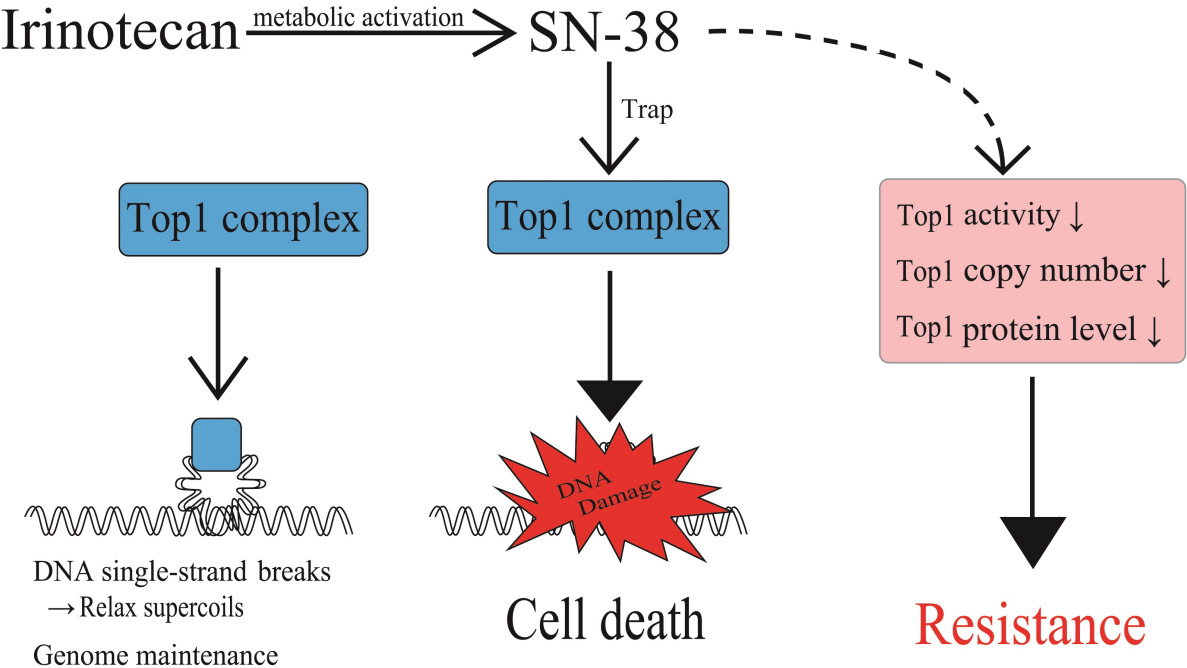

This is an anti-cancer medication used to treat colon cancer and small cell lung cancer

It is in the DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor class of drugs – it blocks the topoisomerase I enzyme, resulting in DNA damage and cell death

The symptoms include diarrhoea, sweating, abdominal pain, watery eyes and increased production of spit (saliva)

It can also cause diarrhoea in the first 24 hours, due to acetylcholine release, leading to a cholinergic syndrome.

A Brain Teaser

A 45-year-old man with schizophrenia taking chlorpromazine develops a bilateral resting tremor.

What side-effect of antipsychotic medication is this an example of?

A: Tardive dyskinesia

B: Parkinsonism

C: Acute dystonia

D: Akathisia

E: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Answers

The answer is B – Parkinsonism.

The correct answer is Parkinsonism. This side effect of antipsychotic medication, such as chlorpromazine, is characterised by the presence of a resting tremor, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity and postural instability. These symptoms are due to the dopamine-blocking effects of these medications in the basal ganglia, which results in an imbalance between dopamine and acetylcholine activity. This mirrors the pathophysiology seen in Parkinson’s disease itself, hence the term ‘Parkinsonism’.

Tardive dyskinesia is another potential side-effect of antipsychotic medication usage but it is not the correct answer in this case. Tardive dyskinesia refers to late-onset involuntary movements that typically affect the orofacial muscles leading to grimacing, tongue protrusion and lip-smacking behaviour. It can also affect limb and trunk muscles causing choreoathetoid movements.

Acute dystonia is incorrect because it refers to sudden onset muscle spasms that can lead to abnormal postures. It is often painful and can occur within hours to days after starting an antipsychotic medication. In this case, our patient has a bilateral resting tremor rather than muscle spasms or abnormal postures.

Akathisia is another possible side-effect of antipsychotics, however it doesn’t match our scenario either. Akathisia presents as a subjective feeling of restlessness often accompanied by fidgeting movements or pacing around. It does not cause a resting tremor.

Finally, Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is a serious but rare complication of antipsychotic use characterised by fever, altered mental status, autonomic dysfunction and generalised rigidity (lead-pipe rigidity). While rigidity may be present in Neuroleptic malignant syndrome as well as Parkinsonism, other typical features such as fever and altered mental status are absent in this patient’s presentation making it an unlikely choice for this question.