Ringelmann Effect

Dear Friend,

Hope everyone is enjoying the extra hour sleep today. Though that does come with a trade-off of it becoming dark an hour earlier. This week’s newsletter is sent from the south of Italy, where I am attending my friend’s wedding. It’s also been a nice break to step back and reflect on my last 2 months as a new oncology SpR – these months have gone by in a flash and been overwhelming at times. This short time away gives me a chance to go through what I did well and can do better in the upcoming weeks.

Lately, I’ve been reflecting again on little theories that help make sense of our day-to-day as doctors. This week, I came across something called The Ringelmann Effect, and it struck me as particularly relevant to doctor life.

The Ringelmann Effect

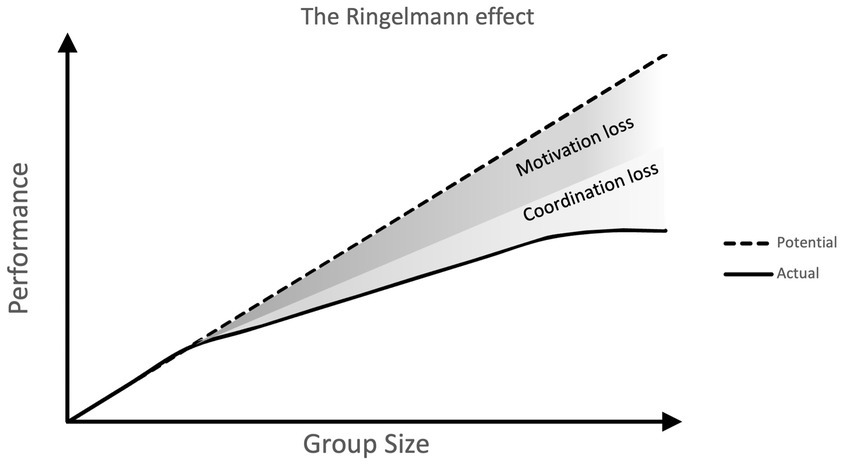

The Ringelmann Effect was first described by a French agricultural engineer, Max Ringelmann, in the early 1900s. He observed that when people worked together on a task — in his case, pulling a rope — the larger the group, the less effort each individual contributed.

In a classic study, Ringelmann found that while two people pulling together produced about 93% of the sum of their individual efforts, groups of eight only managed around 49%. In essence, the more people involved, the less responsibility each person felt to pull their weight.

Later research in psychology confirmed this phenomenon, calling it social loafing — the tendency for individuals to exert less effort when working collectively than when working alone.

Why This Matters in Medicine

We’ve all seen the Ringelmann Effect on the wards. When you’re part of a large team — consultants, registrars, SHOs, FYs, medical students — jobs somehow take longer. Tasks that would fly by on a smaller take list start to linger. Cannulas wait. Discharges sit unsigned. Everyone assumes someone else is on it.

It’s rarely laziness — more often, it’s diffusion of responsibility. When everyone’s name is on the list, it’s easier to think, “someone else will do that.” But in medicine, that assumption can be dangerous. A missed cannula might just be inconvenient; a missed escalation could be critical.

Guarding Against the Effect

So, how do we protect against this natural human tendency? A few small, practical habits can make a huge difference:

Assign clear ownership. Before the ward round breaks, agree who’s doing what. “I’ll chase the CT,” “You’ll update the family,” “You’ll write the TTO.” Clear division stops diffusion.

Double-check with intention. Even if a job “belongs” to someone else, quickly ask if it’s been done before sign-out. It’s not about mistrust — it’s about patient safety.

Use a visible task list. Whether it’s a shared whiteboard, handover note, or electronic job tracker, make sure everyone can see what’s pending. Transparency breeds accountability.

Own your bit. When you know you’ve got a task, do it fully and promptly. Others will mirror that energy.

The Bigger Picture

I’ve realised that being part of a big team doesn’t mean doing less — it means being even more deliberate about doing your part. The best teams I’ve worked in aren’t necessarily the biggest; they’re the ones where everyone feels personally responsible for the patient’s journey.

So next time you’re on a busy ward round or covering a large team, remember Max Ringelmann and his rope-pulling experiment. The more people pulling, the easier it is to ease off without realising. But in medicine, our rope isn’t abstract — it’s patient care. And every person’s pull matters.

Drug of the week

Bevacizumab

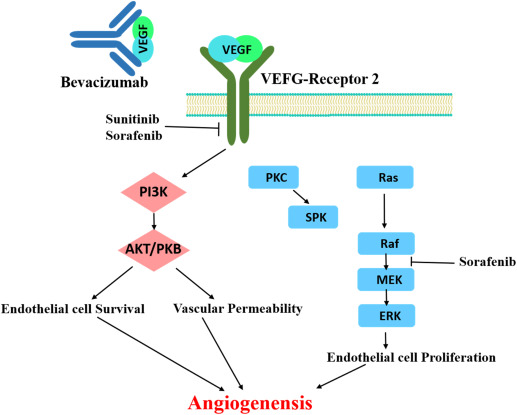

This is a monoclonal antibody that targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key protein involved in angiogenesis — the formation of new blood vessels.

By binding to VEGF, bevacizumab prevents it from activating its receptors on endothelial cells, thereby inhibiting the growth of new blood vessels that supply tumours.

It is used in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of various cancers, including colorectal, lung, renal, ovarian, and glioblastoma.

It is also used off-label for certain eye conditions such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Common side effects include hypertension, fatigue, headache, and proteinuria.

Serious adverse effects include gastrointestinal perforation, impaired wound healing, hemorrhage, thromboembolic events, and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS)

A Brain Teaser

A 22-year-old woman presents to the Emergency Department with confusion, nausea, and tremors. On examination, she is found to have a temperature of 38.5°C and is noted to be sweating profusely. Blood investigations reveal significant hyponatraemia. On further questioning, her friends mentioned that she had taken ‘something’ earlier that evening before her symptoms started.

What substance is the patient most likely to have ingested?

A: Alcohol

B: Cocaine

C: LSD

D: MDMA

E: Methamphetamine

Answers

The answer is E – Viral labyrinthitis.

Viral labyrinthitis is the correct answer. This presents with sudden onset horizontal nystagmus, hearing disturbances, nausea, vomiting and vertigo. Hearing loss and tinnitus are also features of this disease and may vary in severity. This patient’s history of a recent URTI is a useful clue pointing towards viral labyrinthitis, as this often precedes the disease or is present concurrently. In this case, the patient’s right ear is more affected, implying right viral labyrinthitis. Rinne’s and Weber’s tests show sensorineural hearing loss on the right side. This is seen as air conduction > bone bilaterally and Weber’s test lateralises to the unaffected ear. Therefore, the horizontal nystagmus will be towards the unaffected side – in this case, the left side.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is incorrect. This causes vertigo brought on by movement, does not cause hearing loss and presents with rotatory nystagmus. Episodes are short and not present when not moving.

Meniere’s disease is incorrect. This presents with similar features, although it usually is a recurrent condition. The recent URTI also leads us towards viral labyrinthitis as a diagnosis. Meniere’s commonly presents with a sensation of aural fullness which is not present here.

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is incorrect. A posterior circulation TIA or stroke can present with sudden onset vertigo, however, the lack of cardiovascular risk factors present and the recent URTI makes this a less likely diagnosis in this case.

Vestibular neuronitis is incorrect. This also presents after a viral infection with similar features – vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and horizontal nystagmus. The key differentiating point here is the hearing loss and tinnitus seen in the history and examination. These would not be present in vestibular neuronitis as hearing is not affected.