Research Opportunities in Medicine

Dear Friend,

Hope everyone is enjoying the spring weather. I must say, the later sunsets has given me a positive boost and helping me to get through all my on-call shifts. Over the past week, many foundation doctors have confirmed their offers for speciality training which will start this summer. As someone who will be applying for this myself next year, I started to take a quick look at the application process and selection criteria.

One consistent thing that I noticed for almost every speciality was the emphasis on research. For example, in oncology registrar applications, to score a maximum of 10 points in the application form for the research section, this requires at least one first author, or joint-first author, of one or more PubMed-cited original research publications (or in press) related to oncology.

Research is not only important to get publications, but it also demonstrates commitment to speciality which is a large component of the interview. In addition, only by doing research is it possible to present your work at conferences for oral and poster presentations, which is another large component of the application form.

Simiarly, to work as a consultant in many top hospitals, there is now an unoffofical requirement to have a PhD. Given that research is so highly sought out at the higher levels in medicine, the best time to start getting involved is at medical school. This can be difficult as you have to balance this alongside your medical studies. In addition, the opportunities to do research will vary among the different medical schools. I was lucky enough to graduate with 2 first author publications – this helped me to secure an academic foundation post (now called SFP) as well as my first choice IMT job.

That’s why this week, I want to share with you all the different types of research opportunities available. The full article is available to read on In2Med, but here are some key snippets.

The first step to conducting your own research is actually understanding what the different types are. Most people only think about scientific longitudinal experiments – whilst these are great, they take a lot of time to do and you may get negative results. There are many easier types to get involved in which are equally as fruitful. To make it easy for you, we have summarised the different types below:

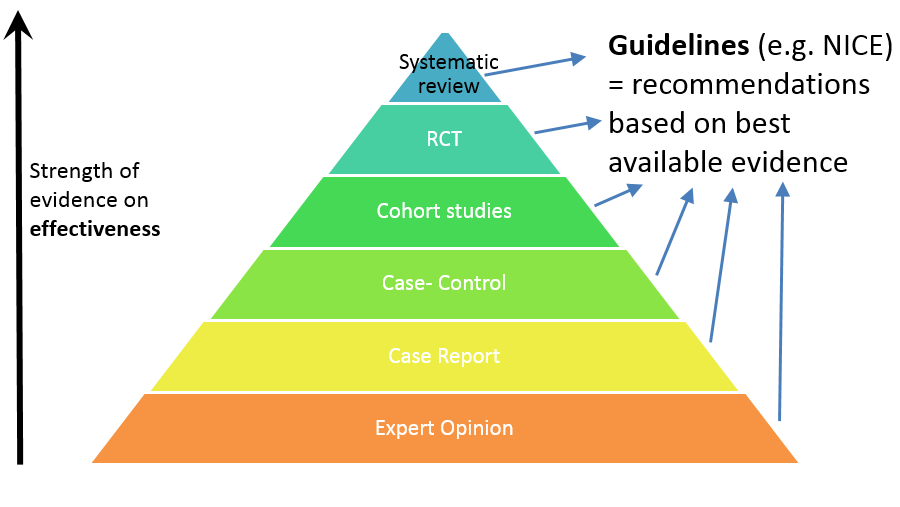

1. Systematic reviews

This is the highest level of research that you can do. A systematic review involves looking at all the research that has been published on a specific question and summarising it. The key here is that is uses very specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

You will need help from a librarian or someone who has done this before to help you. If you are ambitious, systematic reviews can be combined with a meta-analysis, which is a statistical way of combining the results of various papers, and gives you a quantitative way of assessing the data.

Whilst it is the best, it will probably take you the longest amount of time. Depending on the question, you may have to go through anything between 10 and hundreds of papers.

2. Case-control, cohort studies and RCT’s

The case-control studies identify a group of individuals who had developed the disease (the cases) and a comparison of individuals who did not have the disease of interest (controls). The cases and controls are then compared with respect to the frequency of one or more past exposures.

Cohort studies identify people exposed to a particular factor and a comparison group that was not exposed to that factor and measures and compares the incidence of disease in the two groups.

Randomized control trials (RCT’s) test the effectiveness of an intervention and are considered the highest level of evidence for causality. It does this via random sorting of subjects into a experimental group (with intervention being assessed) and control group (placebo or no intervention).

Time and Effort

These studies are in two parts. There is data collection and analysis, which takes up a significant amount of time and there is the write-up which may take comparatively less time. These are big projects and before taking on a project ask your supervisor for rough timescales and be clear about which aspect they want you to get involved in (e.g. Data collection, analysis or write-up?)

How to get involved

1. Find a supervisor with a good project going. Find out whether you will receive credit for your contribution (THIS IS VERY IMPORTANT)

2. Find out exactly how far through the overall project they have progressed. If they are still at the data collecting stage, this could take over a year.

3. Find out how they plan to analyse the results. Many use complex statistics so make sure you can actually do it.

4. Make sure you are interested in the topic!

3. Cross Sectional Studies and Surveys

These are types of observational studies that analyse data from a population, or a representative subset, at a specific point in time. Cross-sectional studies are also known as a transverse study or a prevalence study. Surveys are another method to gather this data at a point in time.

Time and Effort

Varies depending on if you start it from scratch and how much help you get from other people eg. supervisor.

How to get involved

It may be easier to think this kind of study up yourself. If you think of a good question you might like to answer. Perhaps you could do an

NHS staff survey e.g. Association between work satisfaction and extra hours worked.

Once you have thought of an idea consider getting somebody senior to supervise your project for guidance.

Examples

Cross-sectional study – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27467180

4. Case Reports

This is a detailed report of a patients’ symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. It usually describes an unusual or novel occurrence that provide valuable clinical lessons.

Time and Effort

Less than a week: 1000-2000 words

The longest aspect of this is gaining all the data about the patient and obtaining consent. Once you have all the investigations, results and have completed treatment, the write-up is very straightforward, especially if you have been keeping notes throughout.

How to get involved

Finding case reports may be opportunistic. If there is a particularly interesting case ask a more senior doctor if they will supervise your write up.

Alternatively, you can ask doctors and they may have cases waiting to be written up which you could offer to help with.

Key is to be proactive – don’t be afraid of asking. Many new conditions are found by writing up new cases – so you are potentially doing something positive for the world.

Examples

Read the BMJ case report guide and an example by clicking on the following links:

5. Editorials

This is one of the shortest and least time consuming types of research. It aims to provide an opinion which is supported with evidence on a certain topic.

Time and Effort

Will take approx. 3 full working days:

1. One day planning research and collecting evidence.

>2. One day for write up of 1000-1200 words.

3. One day for admin work involved in submitting the article to the journal.

How to get involved

1. Find a journal that you want to submit an editorial to.

2. Look at their style of editorials.

3. Look at the guidelines for authors for that journal.

4. Find a topic to write about that you like.

Examples

Author guidelines for the British Journal of Hospital Medicine:

https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/pb-assets/HMED/Authorguidelines/BJHM_instructions_author.pdf

Example editorial:

www.bmj.com/content/367/bmj.l6594

Summary

I hope this has given you an insight into the various types of studies and research you can get involved in. I would advice getting involved in one piece of strong research, such as primary research where you are obtaining your own data and balancing that alongside a review article. Personally, I found that undertaking a systematic review would be too laborious, but you might be more ambitious than me.

There are more types of research as well, such as letters to the editor and review articles. You can read them in the full blog by clicking the button below.

Hope you found this useful. See you next week!

Drug of the week

Carbamazepine

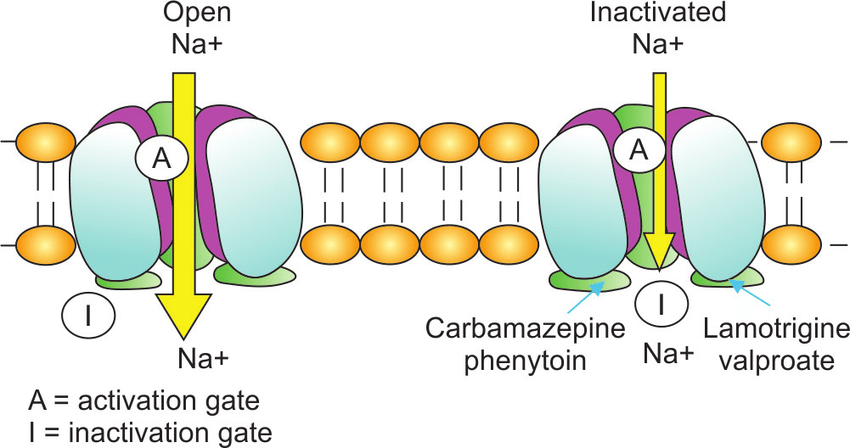

This is an anti-epileptic that blocks sodium channels in the CNS by binding and prolonging the inactivated state of channel.

Its action is use-dependent, so it is more active during seizures characterised by excessive neural activity.

It has teratogenic potential and so is used with caution during pregnancy.

This is used in the management of focal and secondary generalised seizures, as well as trigeminal neuralgia.

It can worsen absence and myoclonic seizures.

A Brain Teaser

A 60-year-old man presents to the emergency department with sudden visual loss in his right eye. He does not describe any pain. On examination, there is a relative afferent pupillary defect and there is a red spot on the retina. He has a past medical history of atherosclerosis.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

A: Central retinal vein occlusion

B: Retinal detachment

C: Ischaemic optic neuropathy

D: Optic neuritis

E: Central retinal artery occlusion

Answers

The answer is E – central retinal artery occlusion.

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the likely diagnosis in this case. It manifests as sudden, painless unilateral visual loss, accompanied by a relative afferent pupillary defect and the presence of a cherry red spot on the retina. Given the specific signs observed in the patient and the absence of indications favoring other conditions, CRAO appears to be the most probable diagnosis.

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is an incorrect diagnosis. While it shares the symptom of sudden, painless unilateral visual loss, CRVO typically presents with widespread hyperemia and multiple retinal hemorrhages resembling a “stormy sunset.” These features are not evident in this scenario, making CRVO an unlikely diagnosis.

Ischemic optic neuropathy is also an incorrect diagnosis. While it presents with painless vision loss, it is characterized by a pale and swollen optic disc, which is not observed in this case.

Optic neuritis is an incorrect diagnosis as well. It typically involves painful vision loss, abnormalities in color vision, and may be associated with multiple sclerosis, none of which are present in this patient.

Retinal detachment is an incorrect diagnosis too. It typically presents with symptoms such as flashing lights, floaters, or a shadow in the peripheral vision, which are not evident in this case. Therefore, it is not the appropriate diagnosis based on the symptoms described.