Medical emergency on a plane

Dear Friend,

Greetings this week from India! After six consecutive long day shifts, I finally flew out for a much-needed break. I’m spending a few days in Amritsar before heading to Mumbai for some sunshine. I wish I could say I’m fully enjoying the food—this was true for the first night, but since then, food poisoning has hit hard. Now, I’m on a diet of home food and toast, hoping to recover in time for the second half of my trip.

This week, I wasn’t sure what to write about—until my flight to India, when I experienced that moment, the one you hear about from colleagues and friends. The one where the announcement comes over the intercom: “Is there a doctor on board? We have a medical emergency.” I had heard the stories, but nothing could have prepared me for this one. So, this week, I want to share my story of a medical emergency on a plane, and what I learned from it.

The Call for Help

About four hours into the night flight from London to Amritsar, the announcement came over the speakers: “Is there a doctor on board? We have a medical emergency.” A 60-year-old man had just come out of the bathroom and suddenly collapsed, falling face-first onto the floor.

I rushed to his side, finding him face down, unresponsive. Two air hostesses had already managed to turn him over, and I immediately noticed blood coming from his nose. I quickly identified myself as a doctor and asked them to stop, urging them to check for a pulse and signs of life. Luckily, he was still breathing, and I could feel a strong carotid pulse. As he began to regain consciousness, I gently placed him in the recovery position.

Assessing the Situation

At the same time, I asked the surrounding passengers to step back to give us space. I started asking the crew and people nearby if anyone knew this man, whether he was traveling alone, or if there were any family members on board.

As he started waking up, he was extremely confused. Blood was still coming from his nose, and he couldn’t remember much. I quickly performed an A-E (Airway, Breathing, Circulation) assessment, borrowing a blood pressure cuff from a nearby passenger to check his vitals. His blood pressure seemed stable, his pupils were reactive, and he appeared hemodynamically stable.

The Patient’s History

The patient, now semi-conscious, told me he was traveling alone. He had no significant medical history and wasn’t on any regular medications, but he did have a history of chronic alcohol use. At that point, it seemed like a textbook case of someone at risk for a cardiac event, possibly a heart attack.

I started mentally running through the potential causes of his collapse—syncope (fainting). I narrowed it down to three main possibilities: neurological, cardiac, and vasovagal. There were no signs of seizure, so I ruled that out. The lack of chest pain and his overall recovery suggested it might be either heart-related (cardiogenic) or a vasovagal episode (a sudden drop in heart rate and blood pressure). As he started feeling a little better, there was a growing possibility it was the latter.

I informed the pilot of the situation, and at that point, the patient seemed stable enough to continue with the flight. I went back to my seat, trying to process what had just happened, and hoped that would be the end of it.

Little did I know, the story was far from over.

The Situation Takes a Turn

About an hour later, I was woken up by the air hostess, who urgently asked me to come quickly. It was the same patient—now vomiting blood. I couldn’t believe it. I rushed back to his side and confirmed that, yes, he was actually vomiting blood. I immediately performed another A-E assessment, and at this point, it was clear we needed to move him to a different part of the plane. The back two rows were already occupied by other passengers who had fainted earlier, so we decided to move him to business class.

I kept monitoring him, doing serial blood pressure checks and reassessing his condition. By this point, I was really concerned that he might have sustained a head injury from the fall. He had hit the floor pretty hard, and with the multiple vomiting episodes, I started wondering if he could have an intracranial bleed—he met the NICE criteria for needing a CT scan. He was also clammy, and now complaining of epigastric discomfort, which made me worried about a heart attack. This was an Asian man, 60 years old, with a high BMI—basically a textbook candidate for a cardiac event. The chronic alcohol use added another layer of concern: was it a variceal bleed (though less likely)?

As his condition worsened, I felt I had no choice but to go to the cockpit and update the pilot. We were now flying over Afghanistan, with just an hour left before landing in Amritsar. I told the pilot that the situation was serious; we could be dealing with any number of issues, and his condition was at high risk of deterioration. The pilot contacted the ground crew, but after some discussion, they decided that the safest course of action was to land in Amritsar, where an ambulance would be waiting for him immediately.

Unqualified Advice from the Cockpit

I was surprised when the pilot asked if the patient had atrial fibrillation—he clearly wasn’t medically trained, and I wasn’t sure why he was asking. He then suggested giving aspirin, and I advised against. There was no way I was going to give aspirin to someone who was actively bleeding.

A Long Wait for Help

At this point, I stayed with the patient, checking on him every 15 minutes, trying to keep him stable. When we finally landed in Amritsar, an ambulance was waiting on the tarmac to take him straight to the hospital. But here’s the kicker—the business class passengers, who had been sitting in their luxurious seats, started complaining about the disturbance. They even requested that the patient be moved back to economy to avoid further disruption in the business class cabin. It was surreal—barely anyone offered to help, even though it was obvious the man was in serious distress.

Helpless Without Equipment

This whole episode really made me realize a couple of things. First, working on the wards, we’re so reliant on tests and investigations. Ideally, this patient would have needed an ECG, blood tests, and a CT head scan. But on a plane, you have nothing. Just your hands, your knowledge, and a very limited toolkit.

Second, I truly appreciated how invaluable an A-E assessment is. When you’re in an uncomfortable situation with so many unknowns, having a basic framework to follow gives you direction. It helped me stay focused and allowed me time to process the situation.

A Changed Perspective

The final thing I realized, though, is just how much I’ve grown. A few years ago, I would have freaked out in this situation—my mind would have raced, and I’d have felt completely overwhelmed. But after my ICU rotation, I felt a sense of calm. It wasn’t easy, but I knew I could handle it if I just stayed calm. That sense of confidence was something I never would’ve expected from myself a few years ago.

This experience is definitely one I won’t forget.

I just hope my flight back home is a little less eventful!

Drug of the week

Levamisole

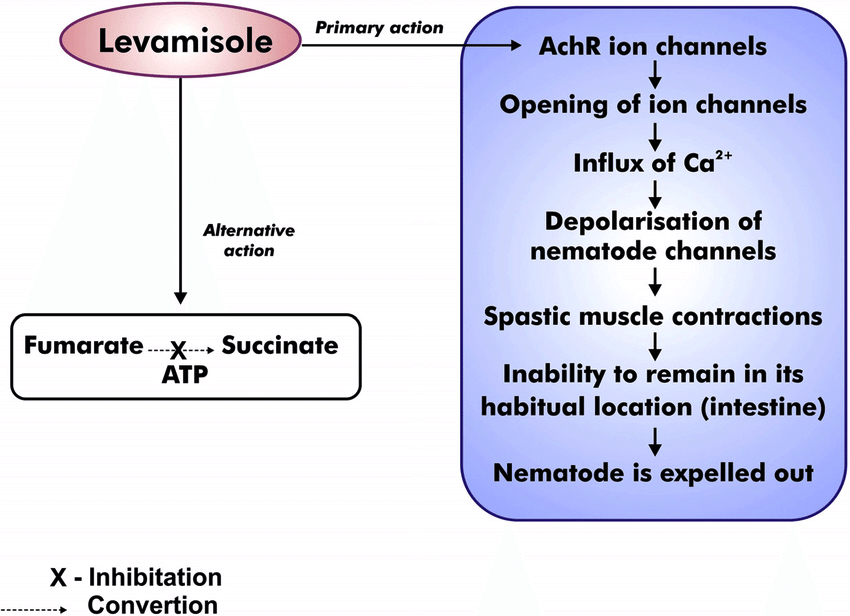

This is a medication used to treat parasitic worm infections, specifically ascariasis and hookworm infections.

Levamisole works as a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist that causes continued stimulation of the parasitic worm muscles, leading to paralysis.

It potentiates the effects of cocaine and is used as cutting agent to increase cocaine volume.

The use of (in particular levamisole-adulterated) cocaine can lead to cocaine-induced vasculitis, a potentially life-threatening disease of which we currently have limited knowledge.

A Brain Teaser

A 55-year-old man who works on a farm presents to the emergency department after being bitten on his left foot by an agitated pig. The bite caused bleeding, and he arrived at the hospital without cleaning the wound.

On the dorsal aspect of his left foot, there is an elliptical-shaped wound approximately 4 cm in diameter, with a clear break in the skin extending 1 cm deep. Soil and dirt are visible within the wound. His immunisation history includes five doses of tetanus vaccine, with the most recent dose administered 8 years ago.

Which option is the best next step?

A: Wound care and tetanus immunoglobulin

B: Wound care and tetanus vaccine

C: Wound care only

D: Wound care, tetanus vaccine and tetanus immunoglobulin

E: No further management needed

Answers

The answer is C – arrange wound care only.

Arrange wound care only is correct. This patient has received all 5 tetanus vaccine doses, with the last dose within the last 10 years. Therefore does not require a booster injection or immunoglobulins, regardless of wound severity. Five doses are considered to provide adequate long-term protection against tetanus. Management should instead focus on thorough wound care, including cleansing and debridement to remove soil and foreign material.

Arrange wound care and tetanus immunoglobulin is incorrect. Regardless of wound severity, if a patient has completed 5 doses of tetanus vaccine within the last 10 years, tetanus booster vaccines and immunoglobulin are not required. Five doses are considered to provide adequate long-term protection against tetanus. This step would be appropriate if the last dose was more than 10 years ago or if the vaccination history was incomplete or unknown.

Arrange wound care and tetanus vaccine is incorrect. This patient has completed 5 doses of tetanus vaccine within the last 10 years. Therefore, tetanus booster vaccines and immunoglobulin are not required, regardless of wound severity. If this patient had completed these doses more than 10 years ago, or if their vaccination history was incomplete or unknown, then this step would be appropriate. Tetanus immunoglobulin would also be given as this wound is at higher risk due to the presence of soil.

Arrange wound care, tetanus vaccine and tetanus immunoglobulin is incorrect as this patient has completed the full 5 doses of tetanus vaccine within the 5 years. In such scenarios, tetanus booster vaccines and immunoglobulin are not required, regardless of wound severity. This step would be appropriate if the last dose was 10 years ago, or if their vaccination history was incomplete or unknown.

No further management required is an incorrect option. While it is true that this patient does not necessitate additional vaccines or immunoglobulins due to their up-to-date vaccination status, they do present with an open wound contaminated with soil and dirt. This necessitates thorough cleaning and debridement to remove any foreign substances followed by appropriate dressing.