International Friends

Dear Friend,

Congratulations on making it through another week. Now, I know surviving a routine week of life shouldn’t usually call for a celebration—but for me, it feels like a real achievement. I’ve just completed my final ever block of four consecutive medical night shifts, and that milestone alone deserves a small victory dance. Only three more in early June… and then I’m free. For life.

In a previous newsletter, I shared how I manage night shifts—how I reverse my sleep schedule, adjust meal times, and transition back to normal life afterwards. But this week, I discovered an unexpected factor that’s made these night shifts far more bearable: having friends across the world.

One of the toughest parts of night shifts is the isolation. While the world sleeps, you’re awake—and when you finally crash, everyone else is up and living their day. It’s a disorienting disconnect from friends, family, and partners (though I’ll admit, that last one might sometimes be a hidden perk). After four nights of talking almost exclusively to unwell patients, it dawned on me: for 48 hours, every conversation I’d had revolved around medicine.

That’s where my international friends came in. While it was 3am for me, it was daytime somewhere else—and suddenly, I wasn’t so alone.

International Friends: The Unsung Heroes of Night Shifts

A typical night shift runs from 9pm to 9am. Most people are asleep by midnight and don’t surface again until around 7am. Even then, they’re usually rushing to get to work. What that means is: for most of the night, there’s no one to talk to—apart from your team, of course.

But here’s the game-changer: international friends.

When your local world is fast asleep, your friends in other time zones can be wide awake. For me, it’s family and friends in India—a 4.5 hour time difference. Knowing that someone I care about will be waking up around 4am has helped me push through the toughest stretch of the night. Whether it’s a quick joke, a motivational message, or just a “you’ve got this,” it’s enough to lift the fog. If you’ve got friends in the U.S. or Australia, even better—different time zones mean more windows of connection during your long night.

So, the takeaway this week is simple: if you’ve ever made friends at a summer camp, while traveling, or during a study exchange—keep in touch. You never know when you’ll need their presence, even virtually. I found that out somewhere between a 4am coffee and a corridor power nap.

Not much else from me this week—just keeping my head down and focusing on getting through my final month of on-calls.

Drug of the week

Fidaxomicin

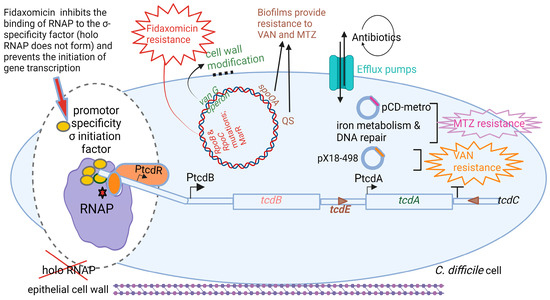

This is the first member of a class of narrow spectrum macrocyclic antibiotic drugs called tiacumicins.

Fidaxomicin is minimally absorbed into the bloodstream when taken orally, is bactericidal, and selectively eradicates pathogenic Clostridioides difficile with relatively little disruption to the multiple species of bacteria that make up the normal, healthy intestinal microbiota.

Fidaxomicin binds to and prevents movement of the “switch regions” of bacterial RNA polymerase.

It is used to treat recurrent clostridium difficile infection, after oral vancomycin.

A Brain Teaser

A pharmaceutical company aims to develop a new screening test to establish the risk of pancreatic cancer. They are currently establishing multiple screening test statistics to build up a report for marketing purposes.

They are using a sample size of 500 patients of which 100 patients tested negative for pancreatic cancer. Out of these 100 patients, 25 are subsequently diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Out of the remaining 400 patients who tested positive, 350 patients had the diagnosis.

What is the specificity of this screening test?

A: 0.60

B: 0.75

C: 0.88

D: 0.93

E: 2.33

Answers

The answer is A – 0.60.

Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)

0.60 is the correct answer. Specificity is defined as the proportion of patients without the condition that has a negative screening test result.

As we already know 100 patients tested negative for the screening test and 25 of these patients had pancreatic cancer, we know that 75 patients tested negative but did not have the diagnosis. Through this, we can calculate that 125 patients did not have the diagnosis and 75 of these patients tested negative as we know that 350 who tested positive had the diagnosis. Specificity is calculated through patients who tested negative over a total number of patients who did not have the diagnosis resulting in the value 75/125 = 0.60.

0.75 is incorrect. This value is the negative predictive value. This is a relative chance of the patients not having a condition should they test negative. This is calculated through the patients who tested negative and do not have pancreatic cancer over the total number of patients who tested negative. This would be 75/100 = 0.75.

0.88 is incorrect. This value is a positive predictive value. Similar to above however this is the relative chance of the patient having the condition if they have a positive result. Using the table above this would be the number of patients with a positive result and have pancreatic cancer (350), over the total number of patients who tested positive (400). Therefore this would be 350/400=0.88.

0.93 is incorrect. This is the sensitivity. This is essentially the opposite of specificity in that it calculated the proportion of patients who have the condition and have a positive test result. This would be 350 patients who have pancreatic cancer and have a positive test, over the total number of patients with pancreatic cancer (375). This would be 350/375=0.95.

2.33 is incorrect. This is the value for the likelihood ratio for a positive test result. This is calculated through the sensitivity /1- specificity.