IMGs – a fair system?

Dear Friend,

Hope you are having a lovely week. This week, I started my new rotation of Intensive Care (ICU). So for the next 3 months, it’s goodbye to shirt and chinos and hello to bright green scrubs. I’m enjoying the prospect of being off the acute medical rota which has been very draining recently, so let’s see how it goes.

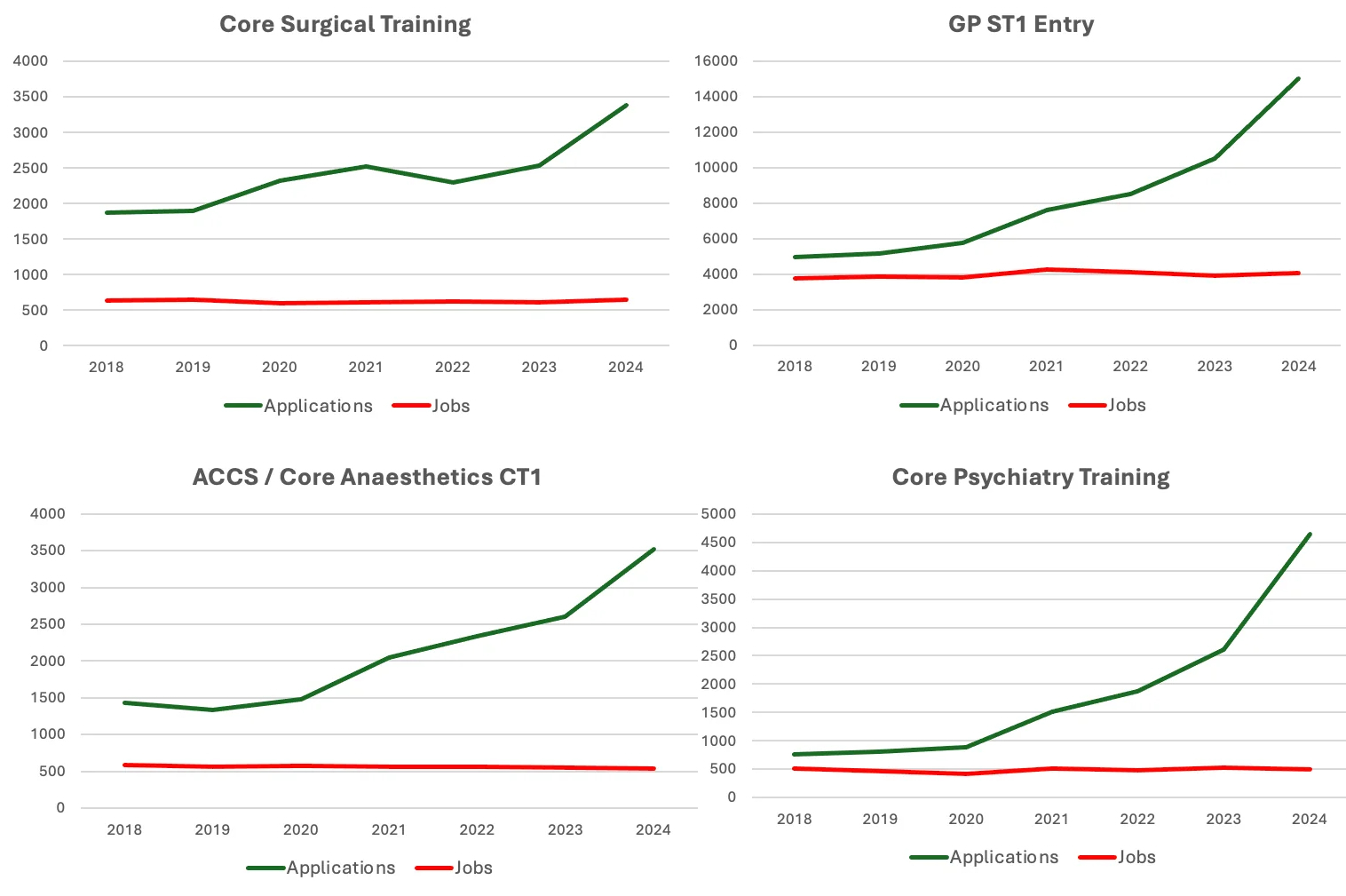

A couple weeks ago I wrote a newsletter about the ultra-high competition ratios to get into specialty training. For example, psychiatry had a ratio of 7 applicants to 1 place. Part of the reason behind this is due to the increase in medical school places as well as international medicine graduates, whilst the number training posts remain pretty static (see photo below).

This week I decided to read a bit more into this, looking specifically at the application process for some specialities. What hit me, is that for certain specialties such as GP and psychiatry, these are ranked only by the MSRA, a computer based exam, without any interview stage. Even for obstetrics and gynaecology, a surgical specialty, if you get into the top 10% of the exam, you bypass the interview and get first-pick at the training posts.

What this means is that if you are an international medicine graduate, in theory, you can enter specialty training directly without having worked a day in the NHS. You have to sit the PLAB 1 and 2 to get GMC registration, but then just have to sit an online exam (MSRA) to get in. You can sit this in your home country as well. Application forms are anonymised and there is no preference for UK based graduates. I was speaking to a few IMGs who said that they managed to enter GP training directly.

The purpose of this mailing list is not to hate on IMGs – far from it. I have a lot of close friends who are IMGs and they are highly valued and required by the NHS. But on the other hand, I can’t help thinking that there are several of my friends who are struggling to get into specialty training, and as such are having to take extra years out, move far from home or even leave the profession together. In terms of training, UK medical graduates have to have passed their medical degree and completed 2 years of foundation training – can we be sure that all IMGs will have accumulated the same level of experience before entering specialty training if they enter directly?

Would it be more fair if there was a preference for UK based graduates? Or perhaps a requirement that IMGs complete at least 1-2 years in the UK before being allowed to enter specialty training? For IMT, whilst there is no set criteria of working in the NHS, as there is an interview stage where they can assess whether you have had sufficient experience in the NHS to enter medical training.

I can’t think of any other country where there wouldn’t be a preference for the home trained graduates. As we face a workforce crisis, wouldn’t making it easier to enter specialty training help more doctors stay in the profession and think more positively about their profession.

Food for thought I guess. I’d love to hear your views on this.

Have a lovely week!

Drug of the week

Metolazone

Metolazone is a diuretic related to the thiazide class.

Metolazone works by inhibiting sodium transport across the epithelium of the renal tubules (mostly in the distal tubules), decreasing sodium reabsorption, and increasing sodium, chloride, and water excretion.

Metolazone is sometimes used together with loop diuretics such as furosemide or bumetanide, but these highly effective combinations can lead to dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities.

A Brain Teaser

A 68-year-old man presents to his GP with worsening dyspnoea on exertion. His medical history includes hypertension, and he is currently taking ramipril.

On examination, bibasal crackles are heard in his chest, and he has bilateral pitting oedema up to the level of his shins. His blood pressure measures 145/89 mmHg.

An outpatient echocardiogram reveals no valvular abnormalities but shows a dilated left ventricle with an estimated ejection fraction of 38%.

What is the most appropriate medication to prescribe next to reduce overall mortality?

A: Bisoprolol

B: Eplerenone

C: Furosemide

D: Losartan

E: Sacubitril-valsartan

Answers

The answer is A – bisoprolol

The patient in question appears to be presenting with symptoms consistent with chronic heart failure. This diagnosis is corroborated by the clinical history of dyspnoea on exertion and findings from the physical examination, which include bibasal crackles and pitting oedema. The echocardiographic evidence of heart failure is confirmed by a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); with this patient’s ejection fraction being 38%, it falls below the normal range, typically above 55%. In managing such cases, initial treatment usually comprises the administration of an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker, introduced sequentially. As this patient is already taking ramipril, it would be clinically judicious to commence bisoprolol as the next pharmacological step. The combined use of ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers targets multiple pathophysiological processes involved in heart failure progression, thereby improving patient outcomes and reducing mortality rates.

Eplerenone, an aldosterone antagonist within the category of potassium-sparing diuretics, has demonstrated efficacy in decreasing mortality among patients with heart failure through inhibition of aldosterone receptors. This action mitigates adverse cardiac remodelling and neurohormonal activation while providing cardioprotective effects. If symptoms persist despite optimal dosing with an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker, introducing eplerenone as adjunctive therapy would be considered appropriate.

It is critical to note that although loop diuretics like furosemide are indispensable for managing fluid overload in heart failure patients, they have not been shown to confer long-term survival advantages. The focus of this question centres on identifying a therapeutic option that offers mortality benefits; hence, while furosemide may provide symptomatic relief from fluid retention, it does not contribute to improved mortality outcomes in individuals with chronic heart failure.

Losartan provides mortality benefits in patients with heart failure by antagonising angiotensin II receptors, thus reducing adverse cardiac remodelling and neurohormonal activation. While ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) are included within first-line management strategies for heart failure, treatment should commence with a beta-blocker unless contraindicated or poorly tolerated by the patient. However, this patient is already taking ramipril so it would be inappropriate to co-prescribe an ARB. Should intolerance arise, losartan may then be considered as an alternative therapeutic option to ramipril for this patient.

Sacubitril-valsartan is indicated for initiation under specialist supervision for individuals who remain symptomatic despite optimal treatment with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers irrespective of their exact LVEF percentage provided it categorises as reduced LVEF. Given that this patient has not yet commenced treatment with a beta-blocker alongside their ACE inhibitor, initiating sacubitril-valsartan at this juncture would be premature and is therefore not recommended.