ICU – Key Tips

Dear Friend,

Does anyone else feel like time is passing by too quickly? One moment it was November, and now Christmas is already just around the corner. It’s true that time tends to fly when you’re enjoying yourself, and I think that might be part of the reason for this feeling.

A significant change in my life recently has been transitioning off the acute medicine rota and starting my rotation in the ICU. For the first time in three years, it’s been a relief to take a break from the fast-paced world of A&E, long ward rounds, and the delays in discharges due to social reasons. I was initially apprehensive about starting in the ICU, but, in fact, it has quickly become one of my most rewarding experiences. This week, I thought I’d share some insights I’ve gained during my first month working in the ICU.

ICU Does Not Cure, It Supports

When people think of the ICU, they often picture ventilators, dialysis machines, and inotropes. While these devices might sound impressive, one thing I’ve learned is that they provide critical organ support, not a cure. For instance, if someone’s lungs aren’t functioning well enough, they may be intubated and placed on a ventilator. Similarly, dialysis can take over the function of the kidneys. However, these interventions don’t address the root cause of the problem. Whether the underlying issue is an infection requiring antibiotics, a heart attack that needs stenting, or a condition that requires surgery, the body itself has to heal. The ICU’s role is to support the organs while the body works to recover, but it does not provide a cure in and of itself.

ICU Has a High Mortality Rate

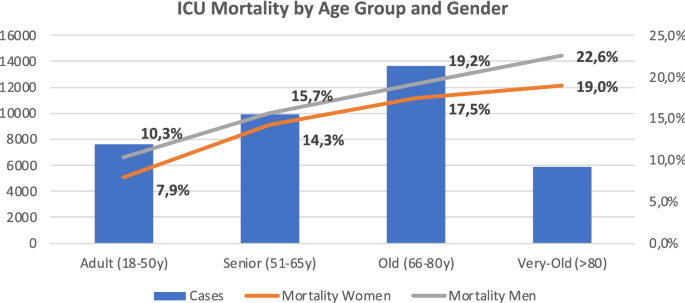

One of the most sobering things I learned during my first week was that approximately 25% of ICU patients will not survive. This figure, of course, varies based on factors like age, comorbidities, and the nature of the illness, but it serves as an average. Another important takeaway is that for each organ failure, the risk of mortality increases by around 15%. So, a patient with 3 or 4 organs failing has a mortality risk of over 50%, as a rough rule of thumb. This realization made me understand just how seriously ill ICU patients are, and how crucial it is to communicate this to their families to manage expectations. Despite our best efforts and medical advancements, we can’t save everyone.

A Great Opportunity to Learn Procedures

If you’re a doctor who enjoys performing procedures, you’ll love your ICU rotation. In just the first month, I’ve had the chance to do arterial lines, central lines, vascath lines for dialysis, and even intubate a patient. There’s something very rewarding about performing these procedures—it’s a tangible way to make a difference in patient care, and it’s a great confidence booster. Plus, the skills you develop in the ICU will be invaluable during your registrar years, making it an excellent environment for learning.

ICU Nurses Are Exceptional

One of the most striking differences between ICU and the wards is the nurse-to-patient ratio. On the wards, one nurse typically cares for 4-8 patients, while in the ICU, most patients receive 1:1 nursing care. ICU nurses are highly skilled and take on a huge range of responsibilities. They not only perform tasks like drawing blood and administering medications (e.g., for electrolyte replacement), but they also manage ventilator settings, adjust sedation levels, and titrate inotropes. If you’re just starting out in the ICU, pay close attention to the nurses—they often have more experience than you and can be a fantastic source of knowledge.

You’ll Become Familiar with Cardiac Arrests

During your ICU rotation, you’ll attend a number of cardiac arrests, both within the unit and throughout the hospital. Part of the ICU role is to manage the airway during these events, so it’s an excellent learning opportunity. While dealing with cardiac arrests can be emotionally challenging, it’s an important experience in your development as a doctor. You’ll gain invaluable insight into acute care management, teamwork, and communication in high-pressure situations.

Summary

So far, my ICU rotation has been one of the best learning experiences of my career. In fact, I believe it should be a core part of the Foundation Year curriculum. The rotation provides a clear understanding of what ICU can—and more importantly, what it cannot—offer, which is crucial for managing patient expectations and handling difficult conversations, such as discussions about Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) orders.

If you have an ICU rotation coming up, make sure to take full advantage of it, even as a medical student. The more you engage and learn, the more you’ll get out of the experience.

Drug of the week

Dexmedetomidine

This is a drug used in humans for sedation.

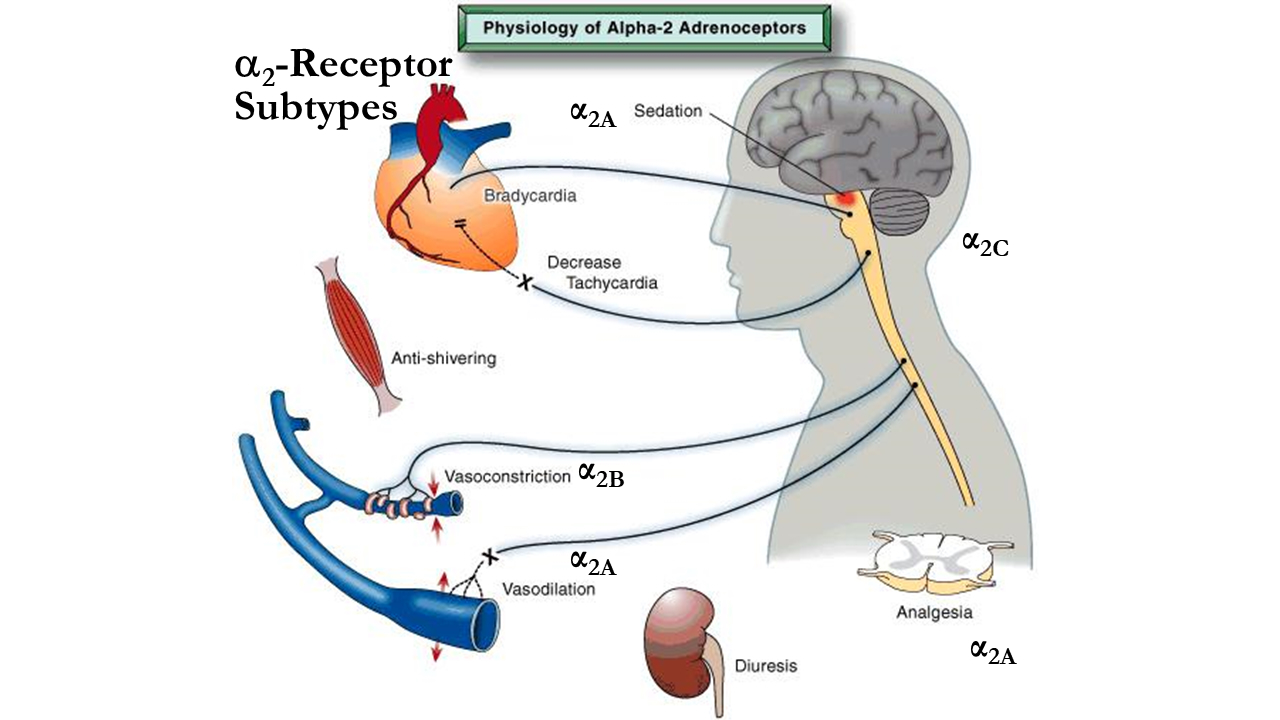

Similar to clonidine, dexmedetomidine is a sympatholytic drug that acts as an agonist of α2-adrenergic receptors in certain parts of the brain.

Dexmedetomidine induces sedation by decreasing activity of noradrenergic neurons in the locus ceruleus in the brain stem, thereby increasing the downstream activity of inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons

A Brain Teaser

A 55-year-old woman presents with a 3-day history of continuous double-vision and vertigo. Her symptoms began with a severe episode of the room spinning followed by associated nausea and vomiting. Recently, she has also noticed left, high-pitched ringing. Her only past medical history includes an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week ago and migraines. She denies any headaches, numbness, or weakness.

Weber’s test lateralises to the right ear, and Rinne’s test is positive (air conduction louder than bone conduction) in both ears. Horizontal nystagmus is seen in both eyes.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

A: Labyrinthisis

B: Meniere’s disease

C: Vestibular migraine

D: Vestibular neuronitis

E: Vestibular schwannoma

Answers

The answer is A – labyrinthitis.

This patient has acute vertigo, horizontal nystagmus, tinnitus, nausea, and vomiting. Weber’s and Rinne’s tests demonstrate left-sided sensorineural hearing loss as Weber’s test lateralises to the unaffected ear (the right ear), and Rinne’s test is positive (normal, air conduction > bone conduction) bilaterally.

Labyrinthitis is correct. Since this patient has features due to both vestibular nerve involvement (vertigo and nystagmus) and labyrinth involvement (hearing disturbances), the likely diagnosis is labyrinthitis. Her recent viral infection is a risk factor for its development as viral labyrinthitis is the most common cause.

Meniere’s disease is incorrect. Although this can have hearing disturbances along with vertigo, patients have episodes of symptoms that remit and recur, lasting from minutes to hours. Patients also report having hearing loss and aural fullness or roaring prior to or during episodes. This patient’s features have been ongoing, making this diagnosis less likely.

Vestibular migraine is incorrect as this does not have hearing disturbances and would also have an associated headache, photophobia, phonophobia, and/or aura. This patient denies having headaches and none of these associated features is present.

Vestibular neuronitis is incorrect. Since this only involves the vestibular nerve, vestibular problems are the only features present (vertigo and nystagmus), without any involvement of the labyrinth (which causes hearing disturbances). Since this patient also has hearing disturbances, both the vestibular nerve and labyrinth are involved, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Vestibular schwannoma is incorrect. Although this can present with vertigo and tinnitus, patients classically have associated features such as an absent corneal reflex or facial nerve palsy. These additional features are not present, and vestibular schwannomas are rarer, making this option less likely.