When I became the patient

Dear Friend,

I don’t usually send out newsletters on Tuesdays, but I wanted to share something personal with you. This past weekend marked the first time in almost two years that I didn’t send out a newsletter—my streak has officially been broken. I wish it were because I was off on a holiday or doing something fun, but the reality is that I ended up being admitted to the hospital last week and spent the weekend receiving IV fluids and antibiotics.

It was a strange experience, transitioning from doctor to patient, especially considering I was admitted to the same hospital where I’ve worked for the past two years. The nurses, doctors, HCAs, and even the catering staff all knew me, which, of course, had its benefits—everyone was incredibly kind. But, I’ll admit, it felt a little awkward at times. If you’ve ever found yourself in a similar situation, I’m sure you can relate.

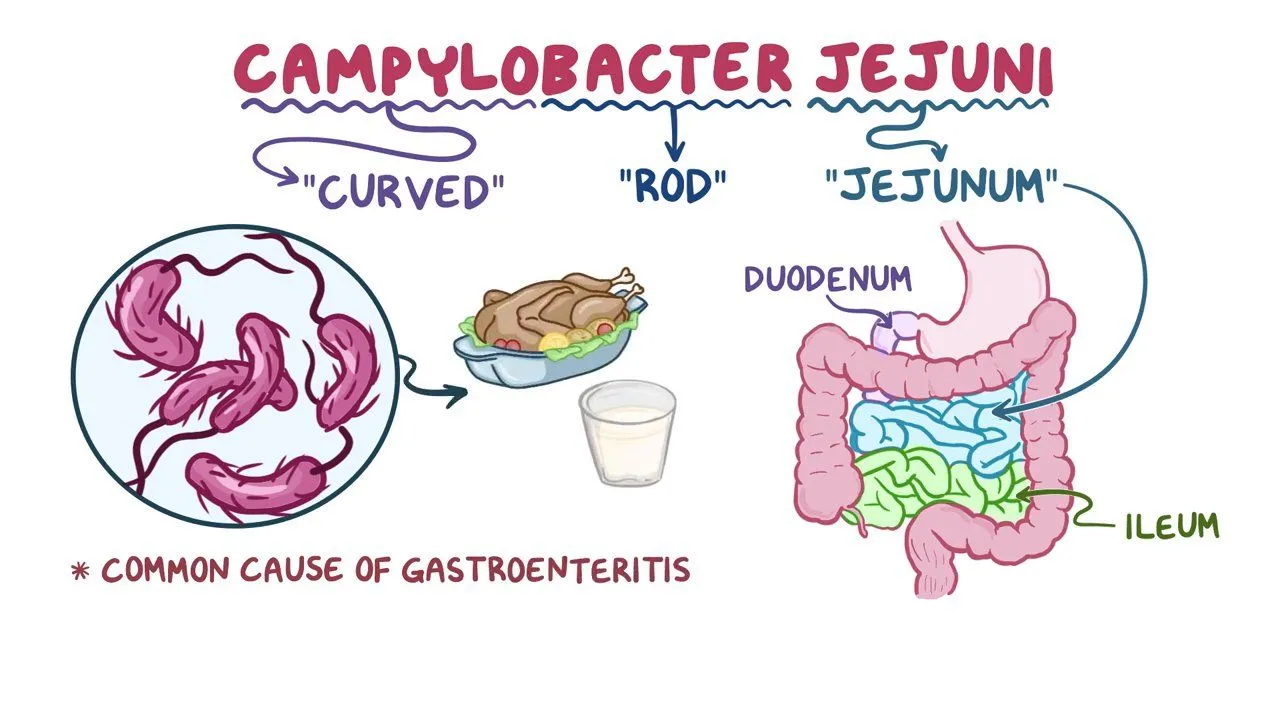

Over the weekend, I was treated for campylobacter gastroenteritis, which caused severe abdominal pain, high fevers, and diarrhea. Thankfully, I’ve now been discharged and am on the mend.

Though it’s not an experience I care to repeat, it’s been eye-opening. As doctors, we often overlook or may struggle to empathize with the small details that can significantly affect a patient’s experience. But being on the other side of the treatment process has highlighted how even the seemingly insignificant things can make a big difference.

This week, I’d like to share some of the key insights I gained from my time as a patient and how these lessons will shape my practice moving forward.

Blood Tests Are More Painful Than I Remember

One of the first things I realized during my hospital stay is just how painful blood tests can be. Maybe it’s because I was unwell and my pain tolerance was lower, but each needle prick felt sharper than I remembered. Over the weekend, I had blood drawn daily—sometimes twice a day for additional tests like viral serology. Fortunately, my veins are easy to find, so they were successful on the first try, but it was still an uncomfortable experience.

As junior doctors, it’s common to order daily blood tests for patients. But how often do we stop to consider whether they really need them? Any investigation, including bloods, should be based on clinical suspicion and whether it will actually impact management. If a patient is stable or improving, perhaps they don’t need daily bloods. For example, if I forget an LFT and it can wait until the next round of tests, I’ll ask myself: Do we really need to do this now, or can it wait?

The Placement of Cannulas Matters

In medical school, we’re taught to insert cannulas into the big veins in the antecubital fossa (ACF) because it’s often the most successful location. However, I quickly realized during my stay that this is a very uncomfortable position for the patient. The first day, I had a cannula in my left ACF, and it was a constant struggle to keep my arm extended. Sleeping with my arm like that was even worse. Every time I bent it, the buzzer would go off, waking me up in the middle of the night.

The next day, a nurse moved the cannula to the back of my hand, and it was a complete game-changer. I could move my hand again, and the discomfort was significantly reduced. Going forward, I’ll be more mindful of cannula placement. If it’s for a short-term procedure (like a scan) or in an emergency, the ACF is fine. But for something like IV fluids over a few days, we should consider a placement that minimizes discomfort for the patient.

The Challenge of Sleeping in Hospital

One of the most frustrating aspects of being in hospital is the difficulty of getting any decent sleep. I was on regular IV paracetamol, fluids, and antibiotics, so I was woken up throughout the night for medication. I also had routine 4-hourly observations—temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure checks. On top of that, a medical emergency in the neighboring bay set off alarms one night, adding to the disruption. No wonder so many patients ask for sleeping pills! As doctors, it’s easy to overlook how deeply these interruptions can affect a patient’s sense of well-being. The takeaway here is to acknowledge the patient’s frustration, even if there’s not much we can do to change the situation.

Summary: A Few Key Takeaways

In conclusion, my recent hospital experience was an eye-opener. There are many small, seemingly insignificant things that can have a major impact on a patient’s experience. These are the things that can often get overlooked when you’re on the other side of the equation, but they matter.

It’s not the start to registrar life I was hoping for—being sick in my first week wasn’t exactly part of the plan. But life happens, and sometimes you just have to roll with it. My focus now is to rest, fully recover, and then get back on track.

I hope your week is off to a good start, and just a heads-up—be careful when cooking chicken. I learned that lesson the hard way!

Drug of the week

Azithromycin

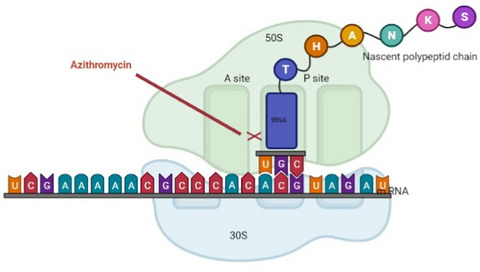

This is a macrolide antibiotic that works by binding to the 50S subunit of the bacterial ribosome, inhibiting protein synthesis and thereby preventing bacterial growth.

It has a long half-life and excellent tissue penetration, which is why short courses (e.g., 3–5 days) are often effective.

Clinically, it’s used to treat a wide range of infections, including respiratory tract infections (like pneumonia, bronchitis, sinusitis), skin and soft tissue infections, some sexually transmitted infections (e.g., chlamydia), and mycobacterial infections.

It’s often preferred over erythromycin because it causes fewer gastrointestinal side effects and has a simpler dosing regimen.

Side effects are usually mild and include gastrointestinal upset (nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain) and headache.

Two important adverse effects to remember are QT prolongation (which can predispose to arrhythmias, particularly torsades de pointes) and hepatotoxicity (though rare).

A Brain Teaser

A 65-year-old man is admitted to the hospital after being found at home in a confused state. He is unable to explain his condition but states that he was admitted for 10 days last month despite records showing his last admission to be 7 months ago. He is unable to recall what secondary school he attended and, after 1 week on the ward, he does not recognise his main doctor’s face. He has a background of hypertension, ischemic stroke and alcoholic liver disease.

Examination shows normal tone, upgoing plantar reflexes on the right and a broad-based gait. There are bilateral cranial nerve 6 (CN 6) palsies associated with nystagmus.

What is the likely diagnosis in this patient?

A: Brain tumour

B: Korsakoff’s syndrome

C: Lewy body dementia

D: Transient global amnesia

E: Vascular dementia

Answers

The answer is B – Korsakoff’s syndrome.

This patient has the triad of confusion, ataxia and ophthalmoplegia, as well as anterograde and retrograde amnesia with confabulation. This is suggestive of Wernicke’s encephalopathy that has progressed to Korsakoff’s syndrome. Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a neurological condition due to longstanding thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, commonly due to chronic alcohol abuse or malnutrition. It manifests as the triad of confusion, ataxia (broad-based gait) and oculomotor dysfunction (seen in this patient as CN 6 palsies and nystagmus). A known complication of untreated Wernicke’s encephalopathy is Korsakoff’s syndrome, which manifests as anterograde and retrograde amnesia as well as confabulation (a patient unconsciously makes up stories to fill a gap in their memory) such as this patient thinking he was admitted to the ward the previous week.

Given that this patient has the triad of Wernicke’s encephalopathy and symptoms of Korsakoff’s syndrome on a background of alcohol abuse, it makes Korsakoff’s syndrome more likely. Brain tumours most commonly present with early signs of increased intracranial pressure (headache, vomiting) and focal neurological deficits.

This patient’s symptoms are not suggestive of Lewy body dementia. Lewy body dementia can be diagnosed by a patient with decreased cognition having 2 or more of the following symptoms: parkinsonism, visual hallucination, waxing-and-waning levels of consciousness and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder.

Transient global amnesia involves retrograde and anterograde amnesia occurring to an individual following a stressful event and lasting commonly between 2-8 hours, but less than 24 hours. This patient’s symptoms and history suggest Korsakoff’s syndrome.

Vascular dementia presents with a step-wise decline in cognition, with early deficits in executive function. It does not cause bilateral CN 6 palsies, nystagmus and ataxia.