Delayed Gratification – the Key to a Medical Career

Dear Friend,

Hope you are having a nice Easter weekend. Unfortunately, I have had to work this weekend, although it appears to be a little less busy in the hospital as people might be away for Easter. To be completely honest with you, this has not been the best week for me. 5 twilight shifts (3pm-midnight) on the back of night shifts last week can leave anyone feeling pretty low. Then, when I compare myself to some of my friends who are away this Easter enjoying their lives, you start to wonder whether the medicine career is worth it.

Most junior doctors I know have questioned whether they regret entering the medical field. Not only is it long with unsociable hours, but in comparison to other degrees, we find that it takes us longer to achieve financial stability, career stability, location stability and family stability. I guess the one key theme is lack of stability. Currently, I am currently revising for my PACES exams – after hopefully passing that, I will then be applying for speciality training. I have no idea where I will be in the UK or whether I will get the speciality of my choice. This makes it harder to plan the rest of my life, in terms of getting a house, settling down etc.

Whilst I was getting overwhelmed with these thoughts this week, one of my friends told me that the key to a successful career is delayed gratification. The idea of short-term pain vs long-term gain. If I keep my head down and stick to it, eventually it will all be worth it. As I started reading into delayed gratification, I came across the Marshmallow experiment.

Therefore, this week, I wanted to share with you how I am trying to perceive a medical career in the context of this experiment. If any of you have had similar wobbles about medicine, hopefully you find it useful too.

During the 1960s, Stanford professor Walter Mischel conducted a series of influential psychological studies. In these experiments, Mischel and his team assessed numerous children aged around 4 or 5 years old, revealing a characteristic now deemed pivotal for success in health, work, and life.

The experiment commenced by inviting each child into a private room, seating them, and placing a marshmallow on the table before them. Here, the researcher proposed a deal to the child.

The proposition was simple: if the child refrained from eating the marshmallow while the researcher was absent, they would receive a second marshmallow as a reward upon the researcher’s return. However, if the child consumed the first marshmallow before the researcher came back, they would not receive a second one.

Thus, the choice presented was between immediate gratification with one treat or delayed gratification with two treats later.

The researcher exited the room for a duration of 15 minutes.

Predictably, some children promptly consumed the marshmallow upon the researcher’s departure. Others squirmed and fidgeted in their seats, attempting to resist temptation but ultimately succumbing after a few minutes. A minority of children managed to wait the entire duration.

Originally published in 1972, this well-known study became dubbed The Marshmallow Experiment. Yet, it was not the treat itself that garnered fame; rather, the intriguing aspect emerged years later.

As time passed and the children matured, subsequent studies were conducted, tracking each child’s development across various domains. The results were striking.

Those children who exhibited the ability to delay gratification and waited for the second marshmallow displayed higher examination scores, reduced rates of substance abuse, lower tendencies toward obesity, superior stress management skills, enhanced social aptitude as reported by their parents, and generally higher scores across a spectrum of life measures.

The researchers continued to monitor each child for over 40 years, consistently finding that those who exercised patience in awaiting the second marshmallow tended to excel in whatever aspect was being measured. Thus, these experiments conclusively demonstrated that the capacity for delayed gratification was paramount for success in life.

This principle resonates widely:

- Opting to postpone watching television to complete homework leads to improved learning outcomes and grades.

- Resisting the impulse to purchase desserts and chips at the store results in healthier eating habits.

- Extending a workout session instead of ending it prematurely with a few more reps leads to increased strength.

In numerous instances, success hinges on prioritising disciplined effort over fleeting distractions, epitomizing the essence of delayed gratification.

What does this mean for medicine?

If you look at a medical career, there are many similarities to the marshmallow experiment. Our degree takes 5/6 years in compared to other degrees which are 3 years. The starting salary for junior doctors in the NHS is also much lower compared to some of the higher paying jobs in the city. We have to do night shifts and work unsociable hours. There are exams and interviews at each step of the process to get to the next level.

In today’s age, where everything is available at our fingertips, the concept of waiting, or delaying gratification is becoming more and more difficult. On social media, our brains are being trained to get hits of dopamine within 5 seconds, the average amount of time we spend flicking through each reel. Therefore, its only natural that the mind will quickly start to wonder whether there is a better future out there rather than being a doctor.

However, when I look around at most consultants, you wouldn’t be able to dispute that most of them seem to have good lives. Most have a healthy work life balance, earn a decent salary and seem content. I think we would all accept that if you want to get ripped and get a 6-pack, you’ll have to fundamentally change your diet and work out a lot. This will mean sacrificing things like junk food and alcohol. Many of us are prepared to do that, but to make it to the top of a difficult career, making those sacrifices is harder. So, surely by applying this same mindset to a medical career, it makes it slightly easier to justify the instability faced in the junior years.

Anyways, I think I’m over my slight wobble this week. Although I don’t know how I’ll feel after working the next two weekends as well (again on night shifts). Being a doctor is hard, and times almost impossible. But hopefully that means that feeling of achievement when you get to the top is even sweeter.

Hope you enjoyed this week’s newsletter. Have a great Easter Monday and see you next week

Drug of the week

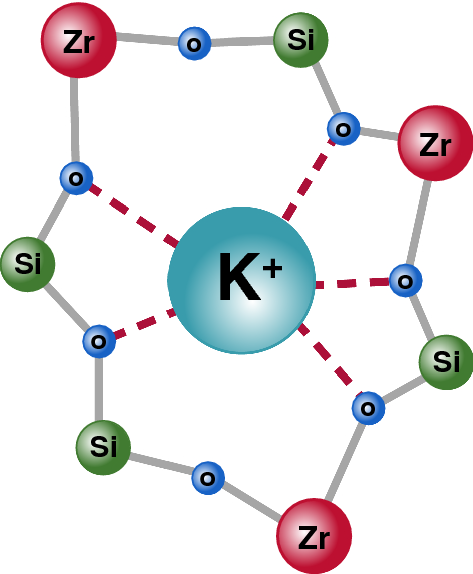

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate

This is a medication which is used in the treatment of hyperkalaemia.

It works by binding potassium ions in the GI tract which are then lost in the stool

As a consequence, it causes the serum potassium level to fall.

The brand name is Lokelma.

The usual dose for adults is 10 g three times a day orally for up to 48 hours, then 10 g once daily as a maintainence dose.

A Brain Teaser

A woman, 8 days postpartum presents to her GP with lower abdominal pain and fevers. She has noticed foul-smelling, blood-stained, purulent vaginal discharge. After undergoing an emergency caesarean delivery, she experienced a moderate postpartum haemorrhage which was promptly controlled by appropriate measures.

Observations:

- Blood pressure: 110/68 mmHg

- Heart rate: 80 bpm

- Temperature: 38.7°C

Endocervical and high vaginal swabs show a mixed growth of streptococci and staphylococci.

What is the most likely cause for her presentation?

A: Endometritis

B: Urinary tract infection

C: Pelvic inflammatory disease

D: Red degeneration

E: Bacterial vaginosis

Answers

The answer is A – endometritis.

Endometritis is the accurate diagnosis in this case. Clinical manifestations such as lower abdominal pain, fever, and malodorous purulent discharge following childbirth strongly suggest endometritis. Typically, endometritis arises from a polymicrobial infection involving both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Predominantly, gram-positive cocci like streptococci and staphylococci are implicated. Swabs taken from the patient corroborate the presence of these bacteria. Endometritis stands as the primary cause of puerperal pyrexia, denoting a fever exceeding 38ºC within the initial two weeks postpartum. This condition is more prevalent among individuals who have undergone cesarean section or experienced postpartum hemorrhage, both applicable to this patient.

Bacterial vaginosis is an incorrect diagnosis. It entails overgrowth of commensal bacteria, primarily Gardnerella vaginalis, triggering vaginal inflammation and a distinct fishy-smelling discharge, notably post-intercourse. The discharge typically exhibits a thin, homogeneous texture, unlike the purulent or blood-stained discharge characteristic of endometritis.

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an inaccurate diagnosis. PID denotes inflammation of the upper genital tract and adjacent structures due to ascending infection from the lower genital tract. While it shares symptoms such as lower abdominal pain and fever with endometritis, PID is predominantly caused by sexually transmitted diseases. However, the absence of a sexually transmitted disease history and the microbiology report’s lack of mention of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae make PID an improbable diagnosis.

Red degeneration of fibroids is an incorrect assessment. This term pertains to acute degeneration and hemorrhage of fibroids, occurring in roughly half of all fibroids during pregnancy. Fibroids necessitate estrogen and adequate blood supply for growth. During pregnancy, elevated estrogen levels accelerate fibroid growth beyond the sustenance capacity of their blood supply, leading to degeneration. However, considering the patient’s 9-day postpartum status, red degeneration of fibroids is an unlikely cause of her symptoms.

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is an incorrect diagnosis. Although UTIs can induce puerperal pyrexia, they are less common than endometritis. UTIs typically manifest with symptoms such as dysuria, malodorous urine, and flank or suprapubic pain. Furthermore, endocervical and high vaginal swabs indicate a genital tract infection rather than a urinary tract infection