Expectancy Theory

Dear Friend,

Towards the end of my IMT, I noticed that my motivation had started to dip. Not in a dramatic way — more like a slow, quiet erosion. The kind where you still show up, still do the work, but something inside feels a little dulled.

I’d find myself staying late to finish jobs properly, chasing results, writing thorough notes — then looking around and realising that others who’d left on time were getting exactly the same feedback, the same outcomes, the same tick in the box.

After a while, it started to feel like extra effort didn’t really matter. That the system couldn’t tell the difference between “good” and “great.” And that realisation was oddly deflating.

Then, almost by accident, I came across something called expectancy theory — a concept from psychology that explained exactly why this feels so hard.

Expectancy theory was first proposed by Victor Vroom, a Yale psychologist, back in 1964. He suggested that our motivation isn’t just about how much we want a goal, but how much we believe our effort will make a difference.

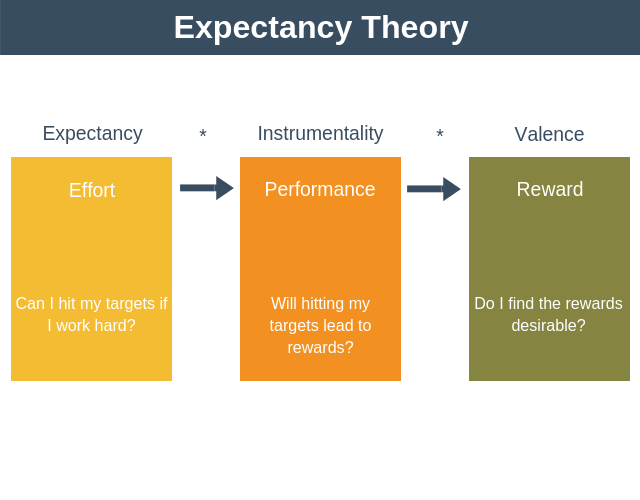

He broke it down into three parts:

Expectancy – If I try harder, will I perform better?

Instrumentality – If I perform better, will I get rewarded?

Valence – Do I actually care about that reward?

When all three line up — when effort feels linked to performance, and performance to something meaningful — motivation flourishes. But when one link breaks, the drive starts to fade.

Over the years, studies have backed this up. Research has shown that people are more motivated when they believe their work will lead to tangible outcomes — whether that’s recognition, pay, or progress. It’s not laziness that kills motivation; it’s learned futility. The quiet sense that no matter how hard you push, nothing changes.

And that, I think, is something many of us in medicine understand a little too well.

In most areas of life, effort and achievement are closely tied. Study more, score higher. Train harder, perform better. But in medicine — particularly in the NHS — the link can feel frustratingly loose.

You can spend hours perfecting your discharge summaries, double-checking every investigation, making sure your patients are well-informed and well-cared for — and yet, when it comes to assessments or progression, all that really matters is whether you’ve met the minimum standard. You either pass or you don’t.

There’s no distinction between good and exceptional.

After a while, that seeps in. You notice colleagues doing the bare minimum and still getting through, and a part of you — the tired, overworked part — starts to wonder, why am I pushing so hard? You start to match the energy around you. The spark dulls a little. You still care, but maybe just a bit less than before.

That’s expectancy theory in motion. When extra effort brings no extra reward, motivation quietly drains away.

Rebuild the links yourself

If the system doesn’t reward your effort, you can rebuild the links yourself.

If the system doesn’t reward effort, you can create your own rewards — your own version of “valence.” Maybe it’s aiming for a publication, improving your communication skills, building confidence with difficult conversations, or mentoring juniors. These goals don’t rely on anyone else’s approval. They reattach effort to outcome.

Because ultimately, expectancy theory holds true — just not always within the boundaries of the NHS. The effort you put in does pay off, even if not immediately or visibly. It’s the groundwork that leads to the job you want, the fellowship you apply for, or the moment you realise you’re quietly competent in ways you weren’t a year ago.

And if one day you decide to move into a different system — whether that’s academia, the corporate world, or private medicine — those habits of graft, curiosity, and pride in your work will matter more than ever.

So when the system feels flat, don’t let it flatten you. Redefine what “reward” means. Tie your effort to something you value, not just what the form asks for.

Because the truth is, expectancy theory doesn’t just describe motivation — it describes hope. And sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do is remind yourself that your effort does lead somewhere, even if the path isn’t marked by tick boxes or assessments.

Keep the faith. Keep the effort. The results will follow — maybe not today, but eventually, in ways that truly count.

Drug of the week

Exemestane

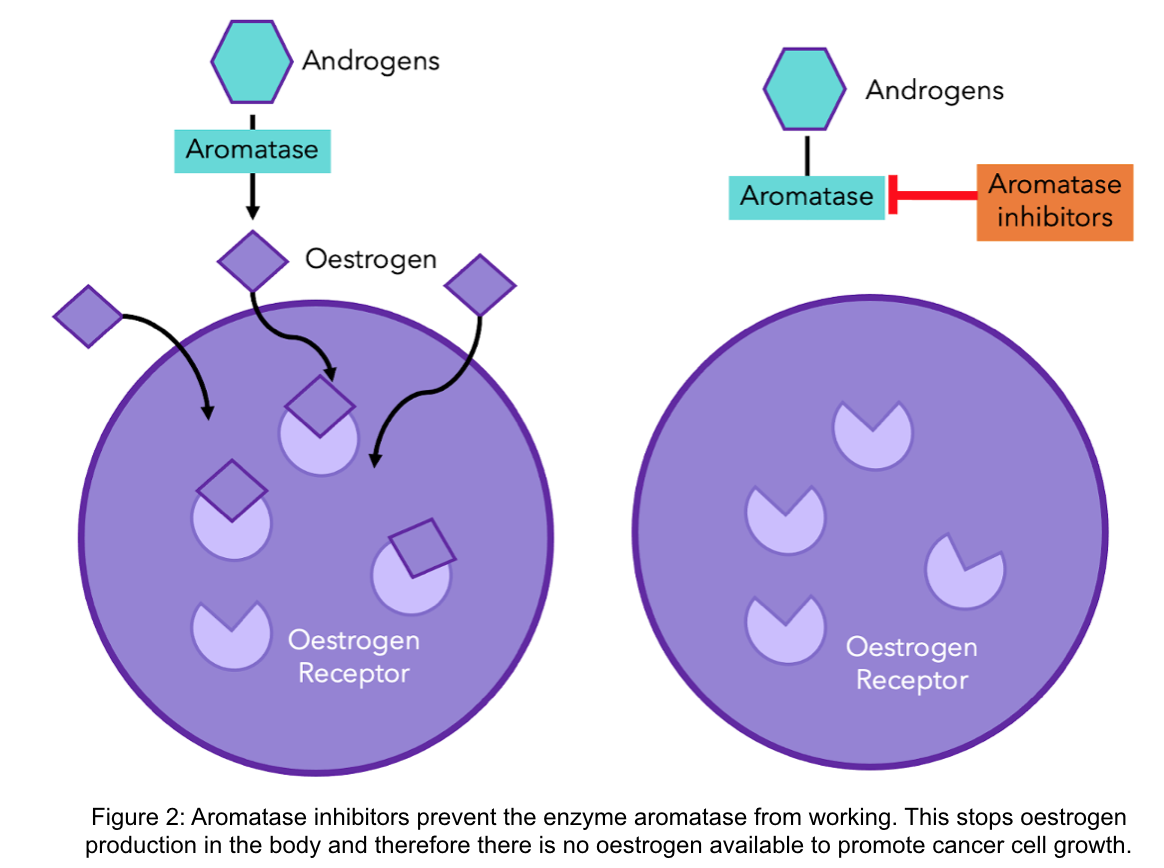

Nivolumab is a monoclonal antibody that boosts the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

It works by blocking the PD-1 receptor on T cells.

Normally, when PD-1 binds to its ligands (PD-L1 or PD-L2) on tumor cells, it turns off the immune response.

By blocking this signal, nivolumab keeps T cells active so they can attack cancer cells.

Nivolumab is used to treat several cancers, including melanoma, lung cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma.

It can be given alone or with other drugs like ipilimumab.

Common side effects include fatigue, rash, itching, and diarrhea.

Serious immune-related side effects can occur, such as inflammation of the lungs (pneumonitis), liver (hepatitis), colon (colitis), or endocrine glands (thyroid or adrenal).

A Brain Teaser

A 59-year-old diabetic man attends his GP with pain in his right ear. He has has the pain for the past 9 weeks but in the last three weeks he has also had some offensive discharge from the ear which is increasing. He has also been having headaches for the past few weeks which are present most of the day on the right side of his head and are not helped by over the counter analgesics.

On examination he is apyrexial, there is some creamy discharge from the opening of the right ear and on otoscopy there is slough and pus in the canal with erythema of the walls. The tympanic membrane is normal.

Which of the following antimicrobials will provide the best cover for the most likely causative agent of this gentleman’s condition?

A: Amoxicillin

B: Ciprofloxacin

C: Flucloxacillin

D: Nitrofurantoin

E: Metronidazole

Answers

The answer is B – ciprofloxacin.

This scenario is describing a patient with diabetes who has developed malignant otitis externa. The key features in the history to suggest this are the length of time, the presence of discharge, the associated headache and his history of diabetes. The normal tympanic membrane indicates this is not an otitis media. The cause of malignant otitis externa is a chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection which becomes invasive and erodes the temporal bone. The most common patient group this occurs in is diabetics. Of the antibiotics suggested here, the one with the best activity against Pseudomonas is ciprofloxacin so this is the correct answer. Flucloxacillin would be the treatment of choice for uncomplicated otitis externa if a systemic therapy was warranted (so he had signs of systemic infection) and amoxicillin would be used in the case of otitis media.

In practice the main topical antibiotics used in otitis externa are ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, the latter would be contraindicated in tympanic membrane perforation as it is ototoxic. The choice between these is generally up to local antibiotic policy although ciprofloxacin is more commonly used as it is less toxic.