GANTT Charts – a life perspective

Dear Friend,

Over the past few weeks, I’ve noticed myself feeling more and more anxious. Not the sharp, immediate kind that you can name — but that low-level hum of unease that sits under the surface and follows you around. I wasn’t sleeping properly. I’d wake up in the middle of the night with my mind running through unfinished tasks. I started getting mouth ulcers again — always my body’s way of telling me something’s off. I felt restless, but I couldn’t put my finger on why.

Eventually, after one particularly jittery morning, the penny dropped.

During IMT, my days were built around lists. Each morning started with a ward round and a clipboard full of jobs. I’d spend the day working through them — discharge summaries, bloods, scans, calls — and by the end of the shift, I’d have that quiet satisfaction of completion. The page would be clear. The list done. I could leave it behind, mentally and physically, as I walked out of the hospital doors.

Even outside work, I’d lived by the same structure. I had goals — exams, getting my training number, finishing my book — and I was laser-focused on completing them. Somewhere deep down, I’d convinced myself that once I’d ticked those boxes, life would finally settle. That I’d reach a kind of calm plateau where everything was under control and I could just… be.

But of course, that’s not how life works.

My new job is completely different. I’m now looking after patients cancer — and there’s no neat end point. You don’t “fix” these problems; you manage them, continuously. There’s always a new query, a letter to chase, results to review. The list never empties. And that realisation hit me harder than I expected.

Because I’d built my entire sense of productivity — and weirdly, my sense of peace — around the feeling of completion. Now, I couldn’t find it anywhere.

And it wasn’t just work. The same pattern had crept into my personal life. I’d moved into a new house — which meant endless admin, washing, cleaning, sorting bills, gym routines that kept getting bumped down the list. Even after finishing one “to-do,” five new ones would appear. I was constantly chasing the feeling of being done, but life, it turns out, doesn’t work like a ward list.

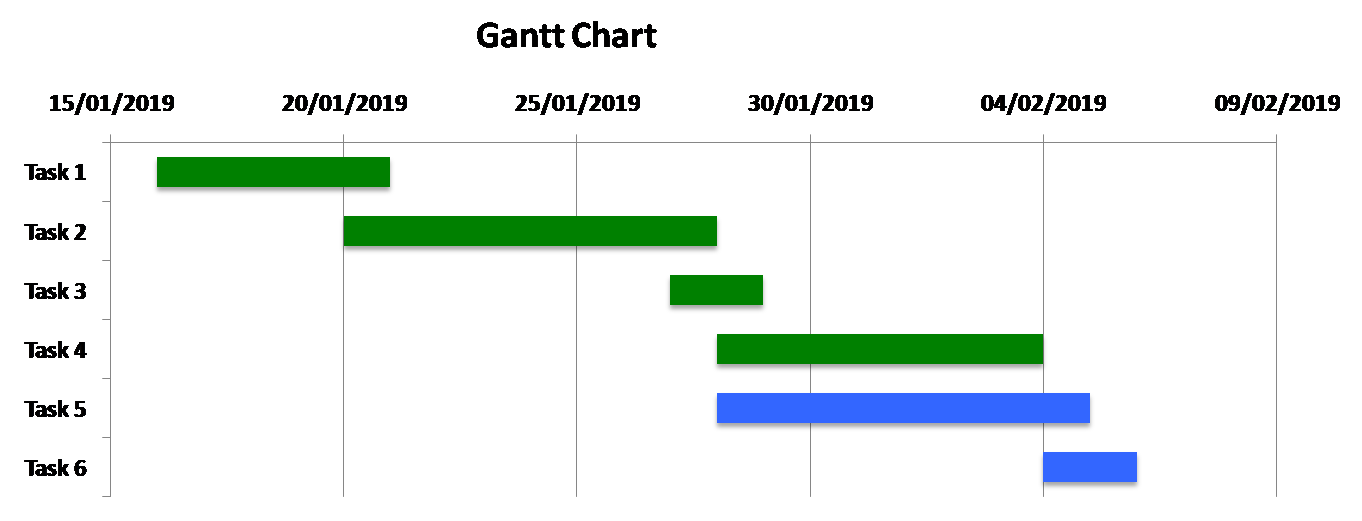

Then, by complete accident, I stumbled across something that changed the way I think: Gantt charts.

Finding calm in the chaos

For those who haven’t used one, a Gantt chart is a project management tool. It maps out tasks over time — showing what’s happening, when, and how different activities overlap. Picture a horizontal timeline: along it, there are bars representing different projects or goals. Some are short and quick, others stretch on for months. Some start before others finish. Together, they create a kind of visual rhythm — a reminder that life doesn’t unfold one task at a time, but many things, moving forward at once.

In a hospital audit, for example, you might start collecting data in week one. By week three, you begin analysis while still tidying up the dataset. Writing the report might start before all results are finalised. The beauty of a Gantt chart is that it accepts this overlap — it’s designed for it. Progress doesn’t depend on completion.

And that’s what I’ve been missing.

I’d been treating life like a checklist, when really, it’s a Gantt chart. The goal isn’t to finish everything; it’s to keep things moving. To know that different parts of your life can be at different stages — some paused, some progressing, some still messy — and that’s okay.

So I tried a small experiment. I sat down and drew my own “life Gantt chart.” Not a detailed spreadsheet — just a simple one on paper. Work projects. Exercise. Writing. Relationships. Home. Even rest. Seeing them side by side — overlapping, evolving — made something in me unclench. It was the first time I’d given myself permission not to have everything neatly tied up.

Because the truth is, nothing in adult life finishes completely. There’s no final discharge summary for “house admin,” no certificate that says “you’ve now completed personal growth.” The trick, I think, is to learn to live in motion — to find peace not in crossing the finish line, but in knowing you’re on track.

Since then, I’ve felt lighter. The ulcers are healing, the sleep’s improving. I still have the same number of tasks, but the pressure feels different — less like a race, more like a rhythm. I’ve even started enjoying the small moments again: coffee in the morning sun, a walk after clinic, the quiet feeling that progress doesn’t need to be perfect to be meaningful.

Life will always be a little chaotic. But sometimes, structure doesn’t come from control — it comes from perspective.

And this week, that perspective — a simple Gantt chart — helped me find my footing again.

Drug of the week

Nivolumab

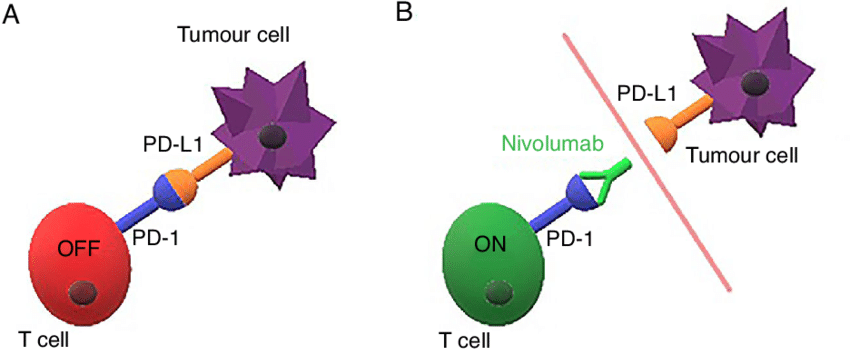

Nivolumab is a monoclonal antibody that boosts the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

It works by blocking the PD-1 receptor on T cells.

Normally, when PD-1 binds to its ligands (PD-L1 or PD-L2) on tumor cells, it turns off the immune response.

By blocking this signal, nivolumab keeps T cells active so they can attack cancer cells.

Nivolumab is used to treat several cancers, including melanoma, lung cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma.

It can be given alone or with other drugs like ipilimumab.

Common side effects include fatigue, rash, itching, and diarrhea.

Serious immune-related side effects can occur, such as inflammation of the lungs (pneumonitis), liver (hepatitis), colon (colitis), or endocrine glands (thyroid or adrenal).

A Brain Teaser

A 28-year-old man presents to the emergency department after getting a metal fragment in his eye while grinding steel. He complains of severe pain, tearing, and photophobia. On examination, his visual acuity is 6/9 in the affected eye. The conjunctiva is injected, and there is mild anterior chamber flare.

What is the most appropriate next step in the assessment of this patient’s eye?

A: Fluorescein staining of the cornea

B: Immediate slip lamp removal of foreign body without further assessment

C: Plain XR of the orbit

D: Start topical antibiotics without examination

E: Tonometry to measure intraocular pressure

Answers

The answer is A – fluorescein staining of the cornea.

Fluorescein staining of the cornea is correct. The patient has sustained a high-risk injury with a metallic fragment to the eye and now has pain, tearing, photophobia, and reduced visual acuity. These symptoms raise concern for corneal abrasion or possible penetrating trauma. Fluorescein staining is the appropriate next step, as it highlights epithelial defects that might not be visible to the naked eye, which can reveal the presence and extent of corneal damage, which is necessary to guide the management of this patient.

Immediate slit-lamp removal of the foreign body without further assessment is incorrect. This is inappropriate because attempting removal before assessing the extent of corneal injury could be dangerous. If there is a penetrating injury, manipulating the eye risks worsening the damage and increasing the chance of vision loss. Fluorescein staining should always be done first to assess the integrity of the cornea.

Plain X-ray of the orbit is incorrect. Imaging such as plain orbital X-ray, is useful when there is suspicion of a retained intraocular metallic foreign body not identified on slit-lamp examination. However, the immediate priority is to determine whether there is surface or penetrating corneal damage, which fluorescein staining can reveal. Imaging comes later in the escalation if clinical assessment suggests a foreign body has penetrated into deeper ocular structures.

Start topical antibiotics without examination is incorrect. While antibiotics may be necessary later to prevent secondary infection, it is inappropriate to start treatment without properly assessing the injury. Simply prescribing antibiotics misses the crucial step of evaluating whether there is a corneal abrasion or a penetrating injury, both of which require specific management.

Tonometry to check intraocular pressure is incorrect. Tonometry is contraindicated when a penetrating eye injury is suspected, as applying pressure to the globe can cause further damage or extrusion of intraocular contents. Since this patient’s mechanism of injury and symptoms raise suspicion of penetration, tonometry would be unsafe at this stage.