Seasonal Affective Disorder

Dear Friend,

I hope everyone’s settling into the darker evenings — and that you’re finding small ways to make the shorter days feel a little brighter. Personally, I’ve found the past week a little harder to wake up, that subtle sluggishness that creeps in when the sunlight starts to fade earlier and earlier. It’s that time of year when the coffee intake rises and motivation can quietly dip.

This week, I’ve been reading about something that perfectly captures this feeling: Seasonal Affective Disorder, or SAD — a reminder that our minds and bodies are more intertwined with daylight than we often realise.

What Is Seasonal Affective Disorder?

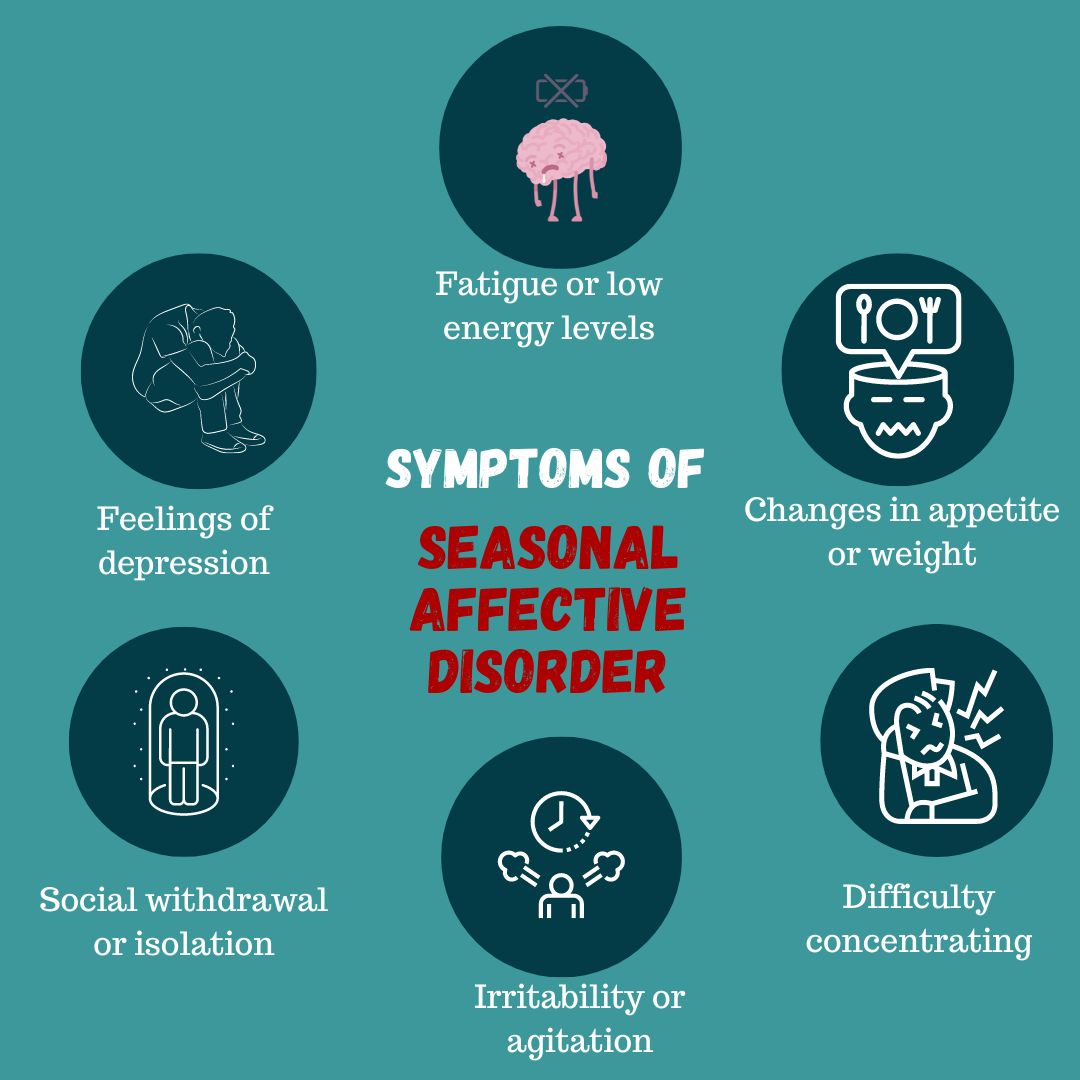

Seasonal Affective Disorder is a type of depression that follows a seasonal pattern — typically beginning in autumn or winter, when daylight hours shorten, and lifting in the spring.

It was first formally described in the 1980s by psychiatrist Dr. Norman Rosenthal, who noticed that his own mood dipped during the darker months after moving from sunny South Africa to the gloomier Washington, D.C. His observations led to a landmark 1984 paper in Archives of General Psychiatry, confirming that some people experience recurrent depressive episodes linked to seasonal light changes.

Since then, multiple studies have supported the idea that reduced sunlight exposure disrupts our circadian rhythms, decreases serotonin, and increases melatonin — all of which can contribute to fatigue, low mood, and poor concentration.

Why It Matters for Us as Doctors

For doctors, the risk is amplified. We already live in a world of long, irregular shifts — early starts, night shifts, windows without sunlight. Many of us spend the brightest hours of the day indoors, under fluorescent lights, and drive home after sunset.

That means the natural cues that anchor our body clocks are constantly being overridden. Even those without a formal diagnosis of SAD may feel what’s sometimes called “winter blues” — lower energy, irritability, or a quiet sense of disconnection.

And in medicine, where empathy, focus, and communication are core to what we do, even subtle dips in mood can ripple outwards — to colleagues, patients, and our own wellbeing.

How We Can Guard Against It

There’s no perfect fix, but there are practical ways to support ourselves through the darker months:

1. Seek the light, literally.

Whenever you can, get outside during daylight — even ten minutes during lunch can help reset your circadian rhythm. Some doctors use light therapy boxes, which mimic natural sunlight and have strong evidence behind them.

2. Keep your sleep consistent.

Irregular shifts make this tough, but maintaining a pre- and post-shift routine can help your body stabilise. Try to anchor at least one “constant” — like waking up at the same time on non-work days.

3. Move your body.

Exercise remains one of the most effective antidepressants we have — brisk walks, gym sessions, or even gentle yoga can counteract that low-energy cycle.

4. Stay socially connected.

When it’s dark and cold, it’s easy to withdraw — but connection is protective. Grab that post-shift coffee. Message your team group chat. Keep those small rituals alive.

5. Be kind to yourself.

If your motivation dips or your focus wavers, remind yourself: this is physiological as much as psychological. It’s not weakness — it’s light biology.

The Bigger Picture

This time of year reminds me that medicine is not practiced in isolation from the seasons — we’re human before we’re doctors. Just as we monitor our patients for subtle changes, we need to notice them in ourselves too.

So as the days shorten and the wards stay lit, make time to step outside, even briefly. Let the light hit your face. Remember that you’re not alone in feeling the shift — it’s the season talking.

And like all seasons in medicine, this one will pass too.

Drug of the week

Dexamethasone

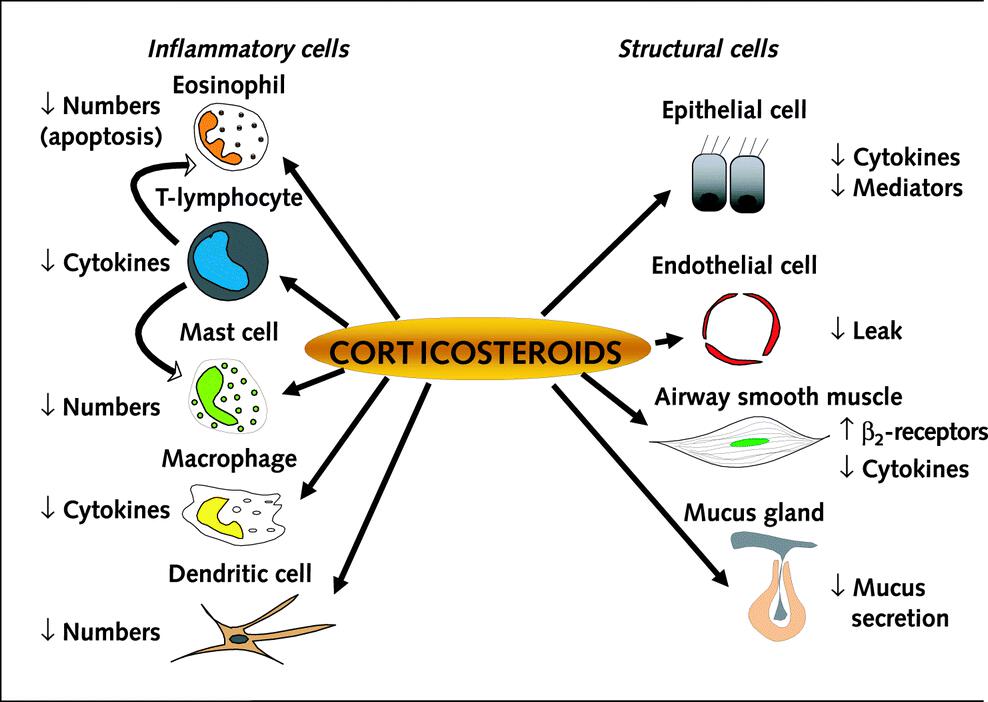

Dexamethasone is a potent synthetic glucocorticoid with powerful anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties.

It works by binding to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors, altering gene expression to suppress the production of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and prostaglandins.

This leads to reduced inflammation, immune activity, and edema.

Clinically, dexamethasone is used in a wide range of conditions — from allergic and autoimmune disorders (like asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus) to cerebral edema, severe COVID-19 infection, and certain cancers as part of chemotherapy regimens or to prevent nausea and vomiting.

It is also used to promote fpetal lung maturity in preterm labor and to manage adrenal insufficiency.

Common side effects include insomnia, increased appetite, mood changes, and weight gain.

Serious adverse effects may involve adrenal suppression, hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, peptic ulceration, and increased susceptibility to infection.

A Brain Teaser

A new screening tool for lower gastrointestinal malignancies has been developed known as the Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT). The researchers would like to identify how effective the test is at picking up colorectal cancer.

The researchers design a study where all participants have a FIT and are then followed up with the gold standard test, colonoscopy.

The researchers found 100 participants positive on the initial FIT, 80 of whom are confirmed to have colorectal cancer on colonoscopy.

900 participants in the initial FIT were negative. 20 of these were later found to have colorectal cancer on colonoscopy.

What is the sensitivity of the test?

A: 8.8%

B: 20%

C: 50%

D: 80%

E: 97.7%

Answers

The answer is D – 80%.

Sensitivity aims to identify how effective a test is at picking up the disease where it is present i.e. a high rate of true positives. This is calculated as TP/(TP+FN).

Here the number of true positives is 80, whilst the number of false negatives is 20.

This makes the calculation: 80/(20+80) = 0.8 = 80%