Pottery Class Paradox

Dear Friend,

I’m happy to share that I’m finally feeling much better and have been discharged from hospital. I’ve completed my course of antibiotics and am steadily on the mend. With some unexpected free time this week (thanks to being off work), I’ve had the chance to reflect on things beyond medicine. Strangely enough, pottery isn’t something I usually think about, but I recently came across a story that’s really stuck with me.

In a pottery class, a teacher divided the students into two groups. The first group was told they’d be graded on the quantity of pots they produced—the more pots, the better. The second group would be graded on quality—their grade would depend on producing just one “perfect” pot.

At the end of the course, something surprising happened: the group focused on quantity ended up making the highest-quality pots too. Why? Because while they churned out dozens of pots, they learned from their mistakes, refined their technique, and improved with practice. The “quality” group, meanwhile, spent their time theorizing, planning, and aiming for perfection—but they had little to show for it.

This story really struck me because it reminds me of the way we learn medicine.

The Trap of Waiting for the “Perfect” Moment

As medical students (and even as junior doctors), it’s tempting to hold back until we feel ready. We think:

“I’ll practice that skill once I’ve revised the theory.”

“I’ll volunteer for the procedure when I know exactly what I’m doing.”

“I’ll write that audit/QIP once I’ve read more about the guidelines.”

But in medicine, waiting for the perfect moment rarely works. Just like the pottery students aiming for one perfect pot, we risk getting stuck in endless planning and self-doubt.

The Power of Reps

The reality is that progress comes from repetition. You don’t get good at bloods by reading about venepuncture—you get good by doing it, again and again, on different patients, under different circumstances.

The first few cannulas may be clumsy. Your first discharge summary may take an hour. Your first patient explanation may feel awkward. But each attempt is a “pot” that teaches you something.

As junior doctors, we sometimes forget that competence is built through reps, not through perfection on the first try.

How I’m Applying This Lesson

Recently, I noticed myself hesitating before volunteering for procedures on ward rounds. I’d tell myself: “Maybe tomorrow, when I’ve revised it.” But then I remembered the pottery class paradox.

Now, I try to reframe it: every attempt is a rep, another pot, another chance to improve. I don’t need to be perfect—I just need to keep showing up. And honestly, the more I do, the less intimidating it feels.

A Few Key Takeaways

In summary, the pottery paradox tells us not to wait for the “perfect” moment to start—you’ll learn faster by doing. Quantity leads to quality—repetition builds skill. Medicine is a craft: every cannula, every note, every conversation is another pot on the wheel.

So next time you find yourself hesitating, remember the pottery class paradox. The only way to make better pots is to keep making pots. Just like my new career as on oncology registrar, as much pre-reading as I might do, the only way I am going to learn is by practicing in real life.

Drug of the week

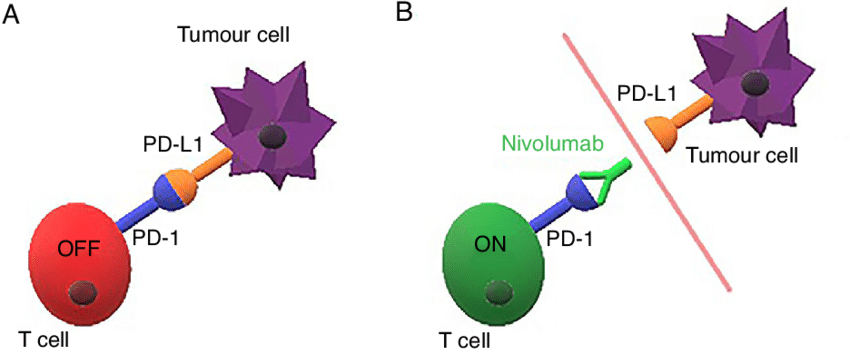

Nivolumab

Nivolumab is a monoclonal antibody and immune checkpoint inhibitor that blocks the PD-1 receptor on T cells, enhancing immune activity against tumour cells.

It is given by IV infusion and used in several cancers, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and head and neck cancers.

Common side effects include fatigue, rash, pruritus, and diarrhoea.

Important adverse effects are immune-related toxicities affecting multiple organs

A Brain Teaser

An 8-year-old girl is brought to the emergency department with worsening redness and swelling around her right eye for the past 2 days.

On examination of the child, there is tenderness and erythema over the right eyelid and during the assessment of her eye movements, she complains of pain and ‘seeing double’. Her temperature is 38°C.

Given the likely diagnosis, what is the most appropriate treatment?

A: IV cefotaxime

B: Oral co-amoxiclav

C: Surgical drainage

D: Topical ciprofloxacin

E: Warm compresses

Answers

The answer is A – IV cefotaxime.

The presence of painful eye movements and visual disturbance (‘seeing double’ referring to diplopia) in the context of a red, swollen, tender eye is concerning for orbital cellulitis. Urgent empirical intravenous antibiotics covering gram-positive and anaerobic organisms (e.g. Intravenous cefotaxime or clindamycin) should be given to all those with suspected orbital cellulitis.

Oral co-amoxiclav with close follow-up is used to manage preseptal cellulitis, which does not cause painful eye movements or visual disturbance and is less likely to cause fever.

Surgical drainage describes the treatment of subperiosteal or orbital abscess, which may rarely complicate orbital cellulitis. These conditions typically present with proptosis, headache (facial, throbbing) and reduced visual acuity, and they more commonly complicate sinusitis (rather than orbital cellulitis). Even in the presence of an abscess, intravenous empirical antibiotics would form an important part of treatment.

Topical ciprofloxacin is used to treat bacterial keratitis, which presents with eye pain, watering and photophobia and is more common in contact lens users. It would not present with eyelid swelling, diplopia or fever.

Warm compresses are used to treat blepharitis, which does present with eyelid swelling and pain, however, it does not cause fever, diplopia or painful eye movements. Further, blepharitis is more likely to involve crusty plaques around the eyelid margin and eyelashes.