Practical procedures

Dear Friend,

Happy Valentine’s Day, everyone! I’m currently on my seventh consecutive shift, with two more to go after today. Let’s just say I’m counting down the days until IMT is over and I never have to work this rota again.

This week, I started my rotation on the cardiology ward. One of my patients needed to undergo an urgent MRI with contrast—this dye helps to highlight certain areas on the scan. To administer the contrast, the patient needed a cannula. Given that it was a particularly busy shift and one nurse was covering eight patients, I realized that by the time she had the chance to insert the cannula, the scan would be delayed. So, I decided to cannulate the patient myself. First attempt, done—job complete, and we move on.

An hour later, the nurse approached me to express her gratitude. She said, “In all my years of experience, you’re the first doctor to cannulate a patient.” She went on to explain that when she first started, doctors were responsible for drawing blood and inserting cannulas. However, with the increasing presence of phlebotomists and nurses, those tasks have now shifted to them.

It’s interesting to note that, while doctors are performing fewer of these procedures, when nurses or phlebotomists encounter difficulties, it’s often the doctor they turn to for assistance—despite our having far less experience with these tasks. This is especially common during on-call shifts or late at night, when blood samples are urgently needed.

This week, I want to emphasize the importance of keeping your clinical skills sharp. The time you need them most is often when no one else is around to help.

Don’t Fear Failure

I’ll be honest—when I started as an FY1, I was terrible at taking blood, let alone cannulating or doing ABGs. As part of the cohort that lost a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I came out of medical school feeling quite rusty. I had two options: avoid it or keep trying. My first rotation was HPB surgery, and every day, I’d make an effort to try at least one blood test or cannula, even though I often failed. It wasn’t until my renal rotation, during night shifts with no option to fail, that I really honed those skills. By the time I started FY2, I was known as the go-to person for difficult procedures.

You Can Inspire Confidence Through Your Skills

When patients see that you’re competent with procedures, they’re far more likely to trust you and respect your decisions. No patient wants to be treated by a doctor whose hands are shaking while taking blood. Investing time in developing your practical skills can even enhance your ability to clerk patients and make diagnoses.

You Will Be Called for the Tough Cases

As I mentioned before, when nurses or other staff struggle, they’ll turn to you. If you’ve been avoiding procedures out of fear of failure, you might get away with it most of the time. But sooner or later, you’ll face a situation where you’re the only doctor on-call, and you’ll need to handle a difficult case, like a chemotherapy patient or one with a fistula and no visible veins. That’s when it gets really challenging.

Conclusion

I highly recommend practicing and improving your practical skills. When I was starting out, I used to practice taking blood on my parents and girlfriend (probably not ideal for a first date!).

Drug of the week

Lidocaine

Lidocaine, also known as lignocaine is a local anesthetic of the amino amide type.

It is also used to treat ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation

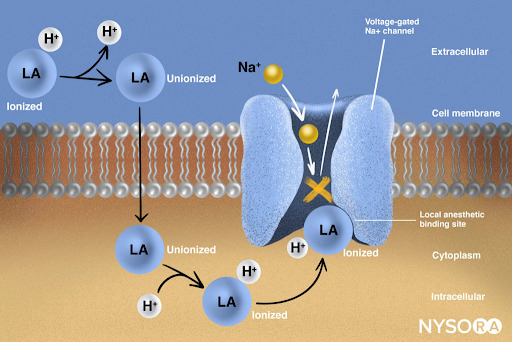

Lidocaine alters signal conduction in neurons by prolonging the inactivation of the fast voltage-gated Na+ channels in the neuronal cell membrane responsible for action potential propagation.

Blocking sodium channels in the conduction system, as well as the muscle cells of the heart, raises the depolarization threshold, making the heart less likely to initiate or conduct early action potentials that may cause an arrhythmia.

A Brain Teaser

A 10-month male infant is brought to the GP by his mother with concerns over using his right hand in preference to the left. He was born via vaginal delivery complicated by shoulder dystocia. He is up to date with vaccinations.

What is the appropriate management for this patient?

A: Reassurance

B: Refer for physiotherapy

C: Refer urgently to paediatrician

D: Request a shoulder X-Ray

E: Review in 2 months

Answers

The answer is C – refer urgently to paediatrician

Refer to the paediatrician is correct. This boy is presenting with early hand preference which points toward cerebral palsy causing weakness to the left side of the body.

Reassurance is incorrect. Hand preference before the age of 12 months is abnormal and needs to be investigated.

Refer to physiotherapy is incorrect. This boy needs to be investigated for cerebral palsy. Although physiotherapy is an integral part of managing cerebral palsy, a referral now is inappropriate as a proper diagnosis has not been made yet.

Request a shoulder X-ray is incorrect. This boy’s main issue is early hand preference; there is no mention of trauma, and the history of shoulder dystocia is irrelevant here as it usually causes Erb’s palsy where the arm hangs limply from the shoulder with flexion of the wrist and fingers due to weakness of muscles innervated by cervical roots C5 and C6.

Review in 2 months is incorrect. There is no point in delaying investigations given the differential diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Reviewing this boy in 2 months would not aid the diagnosis.